REVIEW: To See Heaven in a Wallflower: Heather McAdams, “How Do Ya Like Me Now?” at Firecat Projects

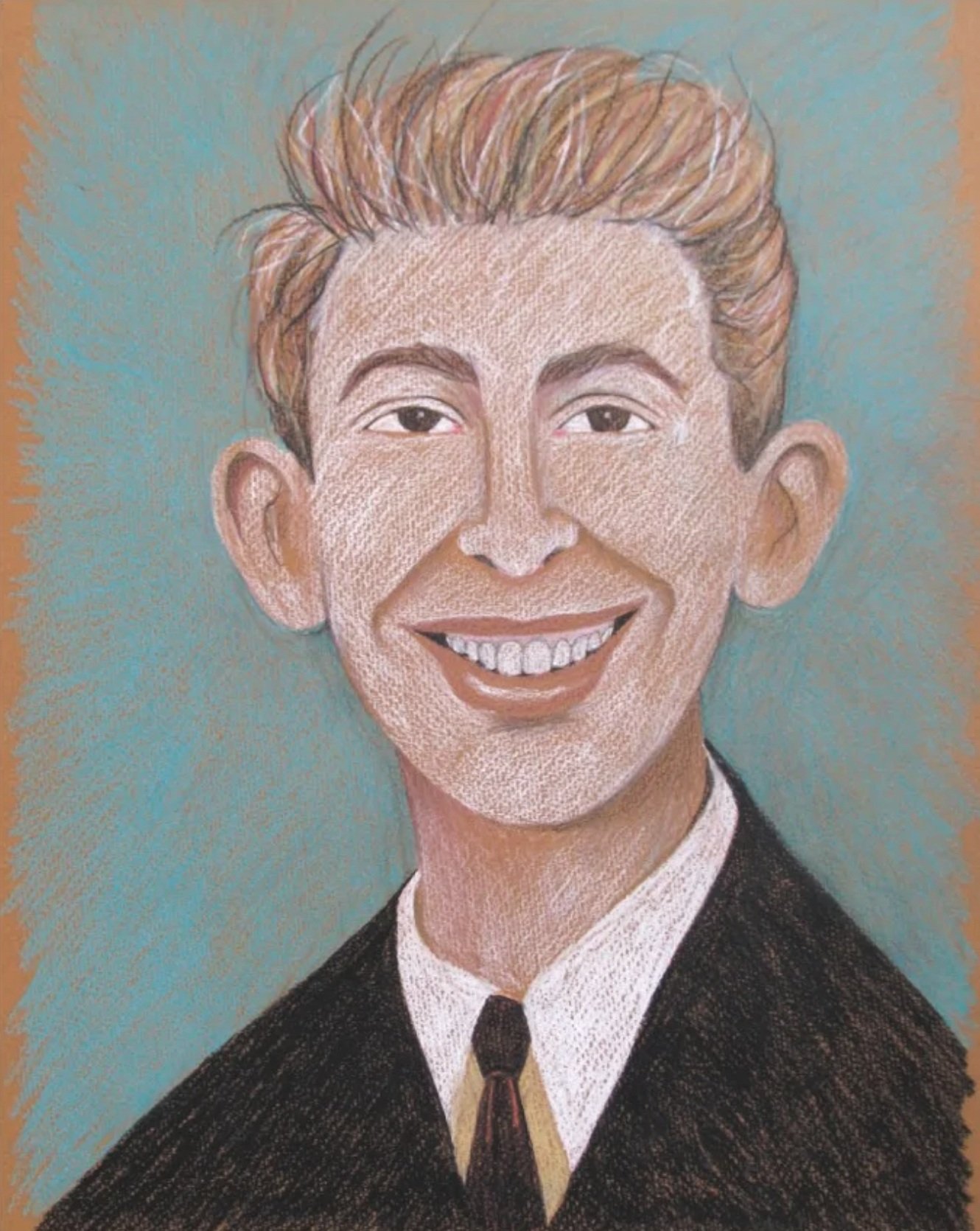

Heather McAdams, Ears, 2024. Derwent colored pencils on toned paper, 14" x 11". Image courtesy the artist and Firecat Projects.

REVIEW

Heather McAdams, “How Do Ya Like Me Now?”

Firecat Projects

2019 N. Damen Ave.

Chicago IL 60647

July 26-Nov 14, 2024

By Charles Venkatesh Young

Heather McAdams was a legendary name in Chicago during the halcyon seventies and eighties, when her wackadoodle comics appeared regularly in the Chicago Reader. The shambling goofballs who frequented her panels—which, unlike the blockheaded vulgarity of the 60s comix scene, opted for risible personal anecdotes—effected a congeniality among viewers that only her rough-around-the-edges style could achieve. Decades after her long stint at the Reader, McAdams’s career is being memorialized at Firecat Projects, where a smorgasbord of work from recent years is on display.

McAdams wasn’t a vocational cartoonist by any means. She started at the Reader to fund her true passion, avant-garde filmmaking. (Every bit as bumbling and aimless as the characters in her panels, when she did make her foray into the world of movies, she frequently introduced herself as “a part-time cartoonist, performance artist, film instructor, junk salesperson, sculptor, painter, movie star, and ardent supporter of the Woolworth’s lunch counter.” (Layer upon layer of camp.) But her cartoons began a fecund artistic practice that came to encompass pencil and watercolor portraits, which make up the bulk of this show.

Heather McAdams, Don King Hair (Chicago Reader Comic) and Now It Can Be Told, date unknown. Ink on paper. Photo by Charles Venkatesh Young. Image courtesy the artist and Firecat Projects.

McAdams is of Mad Magazine progeny, imbuing her sitters with the empty-headed insouciance of the publication’s coverboy: redhead Alfred E. Neuman. Neuman’s awkward gap-toothed grin is the seed from which her subjects emerge: they flash too-big toothy smiles like teenagers at a yearbook photo shoot. (The more confident they are, the dopier the result.) McAdams draws people not as accumulations of lived experience, but as clusters of so many (ridiculous) labels. (That is, when she isn’t drawing her idols. Robert Mitchum appears to be a particular favorite.) From the elated “Happy Clappy Guy” to the smug “Handsome Guy,” the flare-haired “Punk Rock Kid” to the stripe-clad “Big Eyed Girl,” there was not a single trope or physical trait she wasn’t willing to lightly mock. A number of self-portraits at Firecat—variously depicting herself in “Mom’s Hat,” “Cowboy Hat,” and in front of the piano with “Chris”—reveal that McAdams herself wasn’t immune to this indiscriminately derisive gaze.

While the rest of the world lets these mildly embarrassing vignettes languish in camera rolls or family scrapbooks never to be seen again, McAdams takes pains to make them as visible as possible. When you meet eyes with one of McAdams’s sitters, you’ll feel a little more human—pretensions drop, whatever plans you have for tomorrow are put out of mind, and the droll here-and-now makes itself palpable. It can be unpleasant to realize that we’re made of the same stuff as her subjects, that for all our scheming and moralizing, there is a fundamental strangeness to the way we carry on day after day. (Hence the forced smiles, the unnatural head tilts.) But it’s a necessary epiphany. And to McAdams, it’s a joyful one. After all, how bad could things be if these silly billies are behind life’s big choices?

Heather McAdams, Happy Together, date unknown. Pencils on paper. Photo by Charles Venkatesh Young. Image courtesy the artist and Firecat Projects.

I considered comparing McAdams to the German philosopher Martin Heidegger, whose lifelong investigation into “Being”—what I’ve been calling everyday life—came to the same conclusion as McAdams’s oeuvre: life is peculiar. But McAdams isn’t cerebral, she’s colloquial. In her comics and her portraits, she speaks a language of bite-sized tragedies—dumb poses, spilled drinks, car breakdowns—not the dramatic ruptures and self-reconciliations of philosophy. And by showcasing her subtle attunement to the subliminal oddness of day-to-day life—whether it’s through the pointed weirdness of her portraits or the campy punchlines of her cartoons—she imparts it, little by little, to her voracious audience. Imagine (I must, but I’m sure some of you don’t have to) sitting down for lunch at a mind-numbing desk job and seeing one of her cartoons on the front page, feeling it take you by the shoulders and shake you hard while exclaiming in barbaric yawps, “I know your job sucks, but isn’t this all so damn funny?”

Charles Venkatesh Young is a journalist and art critic based in Chicago. He contributes to Newcity and Bridge and is the founder of online arts journal Meaning Without Form (which can be visited at meaningwithoutform.com).

Like what you’re reading? Consider donating a few dollars to our writer’s fund and help us keep publishing every Monday.