REVIEW: David Hockney, “The Arrival of Spring, Normandy, 2020” at the Art Institute of Chicago

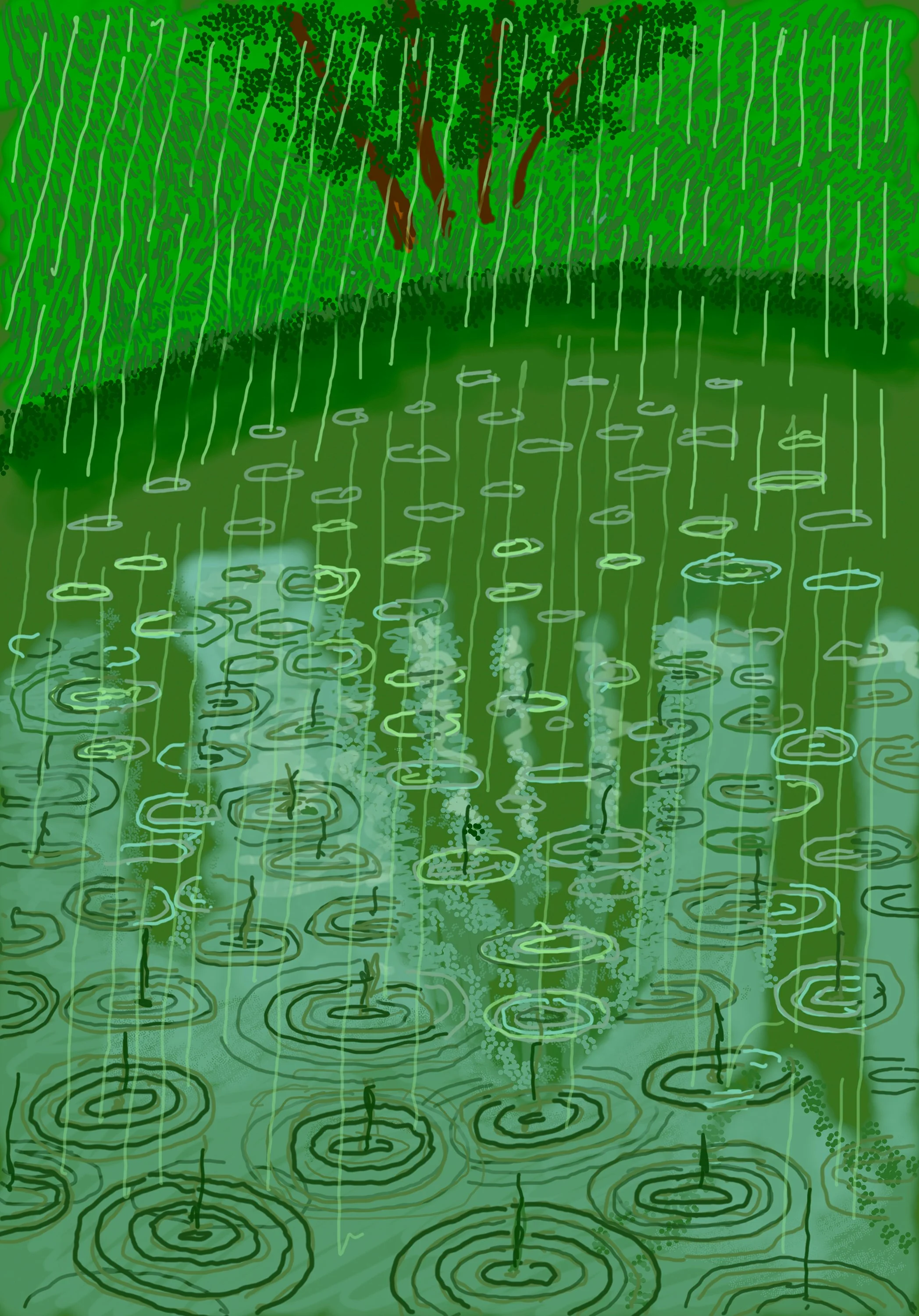

David Hockney. 22nd May 2020, No. 2. © David Hockney. Image courtesy the artist and the Art Institute of Chicago.

REVIEW

The Arrival of Spring, Normandy, 2020

Aug. 20 – Jan. 9, 2023

Art Institute of Chicago

111 S Michigan Ave,

Chicago, IL 60603

By David Sundry

David Hockney’s latest exhibition, The Arrival of Spring, Normandy, 2020, on view at the Art Institute of Chicago roughly coincides with his seventh decade of art making. Hockney is one of the most famous and celebrated artists in the second half of the 20th century. He is an English painter, draughtsman, printmaker, photographer and stage designer. He is also known for experimenting with new technologies, in this case the iPad, and it represents his third major showing of these images, with previous shows in 2011 and 2013.

Hockney’s interest in new technologies began in the late 1970’s and early 1980’s and includes fax machines, photocopiers, and the Quantel Paintbox, an early computer program that allowed an artist to sketch directly on the screen. He also created several series of photocollages using both polaroid and 35mm commercially processed color prints.

Hockney’s work has always been accomplished. The work is witty and stylish, inventive, with a pictorial theatricality that is underpinned by technical virtuosity and refinement. His work has cleverly absorbed a number of modern 20th century styles which he uses to both observe and construct a kind of comedy of manners beginning with his paintings in the late 1960’s of southern California.

The other side of Hockney’s work is based on a continuing series of portraits of friends, lovers, relatives, collectors, and curators. There is a kind of conspiratorial intimacy that is felt and allows Hockney to transcend his borrowed conventions and produce and extend the tradition of portraiture. Hilton Kramer, the legendary art critic for the New York Times and the New Criterion described Hockney’s work as “a kind of 19th-century salon art refurbished from the stockroom of modernism.” And, on some level in this show, Hockney is attempting to revitalize the late 19th-century model of en plein air (open air) painting most famously practiced by Monet. He is extending the landscape tradition through a series of oversize paintings composed of individual panels and, at the same time, developing intimate digital plein air images using the iPad.

David Hockney. 5th March 2020, No. 2. © David Hockney. Image courtesy the artist and the Art Institute of Chicago.

And on many levels Hockney succeeds. The images are painterly, pleasurable. There is a satisfying aesthetic sense of just captured but discreetly observed freshness that is lively and celebratory. And the brightness and flat printed nature of the image suggests a comparison to a kind of superior poster art – think Lautrec – of the late 19th-century. And, in every way, the work succeeds until somehow . . . it doesn’t. After the initial flush of admiration, questions slowly arise, and the images do not seem up to the task. On some level, the work poses no new questions nor aspires to present a set of questions period. It seems the sole goal of the iPad format (besides its convenience and possible ease of revision) is to mimic painting and painterly effects. But these digital painting effects now exist as code, a file of layered saved states, edited, uploaded, more light than mark, devoid of materiality. Unlike Hockney’s cubist photocollages where he inventively used a cheap commercial process devoid of artistic merit to construct works that explored seeing, patterns of human noticing, and new modes of perception along with a successful historic updating of cubist style; these iPad images feel nostalgic with an almost consumerist acceptance of the gee-whiz qualities of the apps rather than an engagement of what might constitute a real digital updating of late 19th and 20th-century modernist conventions, questions that will provide a necessary grounding for a true digital practice.

The images sit on the surface, imprints of digital immediacy, yes, but lacking the tactile gravitas that paint on linen or canvas, watercolor or pencil and conte or pastel on paper possess. It is as if these images only aspire to printed reproductions. In the past, even Hockney’s quick studies in traditional media had a slowness and layered engagement that deepened avenues of feeling, looking and processing. He is often criticized for the ease, accessibility and playfulness of his work as if the apparent lack of angst rendered the whole unserious or intellectuality light. In the past, similar critiques were unfairly levied against Raol Dufy or Bonnard, charges that subsequently failed to trivialize their body of work. There is some basis to apply this critique to Hockney’s often immediate embrace of technology, but not to the body of work as a whole.

David Hockney. 27th April 2020, No. 1. © David Hockney. Image courtesy the artist and the Art Institute of Chicago.

This exhibition is full of admirable and elegant images with wonderfully refined passages: a mixture of precision and slapdash by the hand of a master and the images bear Hockney’s imprint - they look like Hockney paintings. But then this realization makes one wish that they had been realized in the more traditional mediums where the slow material development of the image would provide a bit more “there-ness” to enable the viewer to consume them a bit more slowly – to reflect a bit more.

Like what you’re reading? Consider donating a few dollars to our writer’s fund and help us keep publishing every Monday.