REVIEW: “In the Hour of War: Poetry from Ukraine,” Edited by Carolyn Forché and Ilya Kaminsky

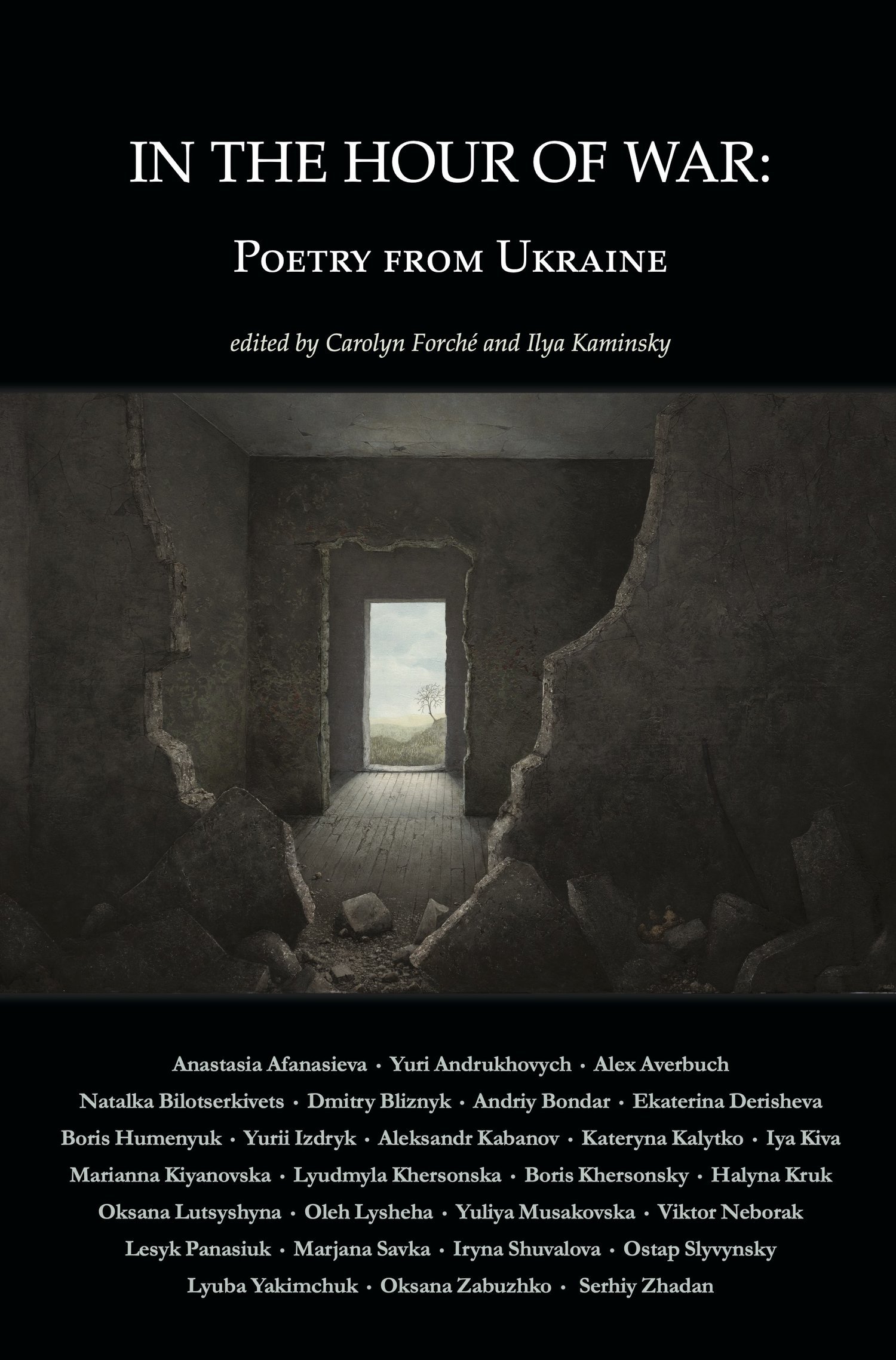

Cover image courtesy Arrowsmith Press.

REVIEW

In the Hour of War: Poetry from Ukraine

Edited by Carolyn Forché and Ilya Kaminsky

Paperback, ($22)

Arrowsmith Press

By Michael Workman

It’s a seeming natural leap to make to conflate the poetry of witness as a lens through which to consider the historical implications of the current rise in use of state-sponsored terrorist violence around the world as a tool for autocratic ambitions. It’s a necessary and urgent reckoning that reverberates across time and geographic borders, and well-needed. Current debates, especially in America, are conducted with the usual lack of interest in subtlety or distinction, marred with all the usual bright line-drawing us-versus-them reductivisms of our irrepressibely binarist masscult public discourse.

It’s tempting as well to enlarge the discussion from the outset into a reflection on the current-moment horrors of Hamas’ Iran-backed pogrom-style massacre of Jewish civilians in Israel, willing to fight normalization by slaughtering babies and elderly people, and machine gunning teenagers in their beds, — and also condemn the “religious-nationalist-settler” wing (Thomas Friedman’s term) seeking an Israeli scorched-earth retaliation, largely also against civilians, as Hamas retreats back behind their land-locked human shields in the Palestinian population of Gaza. Tempting, as well, to articulate that cohort’s recent attack on an independent judiciary, and democratic checks and balances.

This anthology is also about the effects of state-sponsored terrorist violence, in this case Putin’s. No government that embraces the use of weaponized terror should be regarded as a legitimate authority, and these latest examples certainly do conjure what Forché described as the “evil and its embodiments” that poetic language seeks to reconcile. It’s never more clear in this collection than in the horrific near-absurdism of Viktor Neborak’s Flying Head, right from its first stanza:

It lifts up, like a head

a head chopped off a derelict.

It speaks, and then again

and again, its other-worldly words:

I AM THE FLYING HEAD!

Or, when Lesyk Panasiuk writes in Our faces, tossed about this land:

Please explain this poem a soldier asks our neighbors

while tossing

them against walls

Asks our neighbors to explain a line break

while raping our wives a third time a fourth time a fifth

asks children

of our neighbors to explain while they are locked up in the basement

Please explain this poem a soldier asks

while our neighbors

are slaughtered

Asks our neighbors to explain a line break

while our children

are without food in a basement

Our faces tremble

As if from the wind

This volume, a collective poetics actively struggling for a response to the evidence of what latest atrocities state-sponsored terrorism has rendered in Ukraine, delivers a collected poetics certainly larger than language that, vacated by the shock of this most appalling form of violence in its immediate aftermath, any sound mind could suffuse or contain. Iran, aligned with Russia alongside North Korea and China, is just the newest latest aggressor, and with much less geographic area to engage in its conflict. Putin’s Russia staggers ahead of its aftermath, the wreckage of that despot’s illegal, cruel and heart-wrenching “special operation” campaign against the Ukrainian people presented here, in just vivid enough human detail. It also continues the poetry of witness tradition of the twenty-first century in large part defined by Forché’s scholarship, who joins forces in this volume with co-editor Ilya Kaminsky to shepherd through the work of these twenty-seven poets, and numerous translators.

As pointed out in other reviews, there is a practicality that foregrounds the day to day of Ukrainian life depicted – what to pack? How to travel? Eat? Clean your weapon? Throughout the daily attempt to survive, there resounds the presence and fear of what Dmitry Bliznyk describes in this excerpt from his poem Take immortality, God, but give as “missiles’ needlework:”

Watch: a mad tailor makes of a city a headless costume without

Hands. This is your human being, God, and not

A retail display mannequin.

The future is a door of mud

glass, the color of raw diamond.

This door opens inside

my chest every moment.

Each breath in

is a breath out,

sometimes faster

sometimes not at all.

In a time of war

the future jumps out

like a frog, no, like a grasshopper —

one second —

and there is nothing: no future —

just emptiness, pulsating.

The emptiness claws forward against the living, arriving from all sides, filling the moments in a city under mandatory nighttime blackout until, as Borys Humenyuk writes in his poem when you clean your weapon, eventually ”you and the war are one.” Sitting with these images, what slowly emerges are the ways in which poetry reads us, in the sense that just as the experiences grasped after here are larger than the language, our collective human endeavor is also smaller than its sum and total, a puzzle of recurring themes and tropes, visible in any manner of assembly.

As Czeslaw Milosz noted, “both individuals and human societies are constantly discovering new dimensions accessible only to direct experience,” and in this collection, there unfold perspectives and chronicles rooted in Celan’s encounter with the Holocaust that echo throughout history, from the Ukrainian war and numerous other blood-drenched autocratic baby men (incapable of even governing themselves) reigns — Milošević, Pinochet, Pol Pot, Karamira and his cohort in Rwanda, and the poets who responded to their repugnant histories and to war violence in general: Silajdžić on the Serbian and Sophal Leng Stagg’s poetry on the Cambodian genocides and, of course, Kaminsky on the war in Moldova’s Transnistria region at the end of the USSR (whose fate is also tied to the outcome in Ukraine now). These are societal movements that, after all, that poetry, as Milsoz noted in A Few Words on Poetry, is bound “more rigorously than any other mode of expression, to the physical and spiritual Movement of which it is a generator and a guide,” (with its implied dialecticals, including the consistent return of evil) and that through which it is conceived, “every historical period receives its definite shape through poetry.” In that attempt to redefine, that impulse for fresh possibilities, a tinge of hope emerges in Yurii Izdryk’s New Song of Silence when he writes:

It was evening, when we left it was evening

and snow fell into a time

where Russian ship drowned

and dogs were tossed at us

We weren’t heroes or soldiers, we

run, and behind us memories stood

among bombed out grocery stores and streets

which still had our faces

We were the last from our bomb shelter

who dared to jump

into the car — cats, dogs, mothers

a snake wrapped into a wool blanket

we were the last who

stopped

It’s in this collection that the non amonis moria, the impulsive longing to record an honest assessment of the individual life and worth of one’s lived experience emerges in the still-living moment, but also that of mourning and a way of carrying the news — the kwibuka poems written in response to the Rwandan massacres are cited as of immediate relevance. I would also add the effects of maanso poetry that exploded as a uniquely Somalian mode transmitted by the cheap medium of cassette tapes, in the protest work of Hadrawi and other contemporaries, is also pertinent as experiential records of daily existence during, or after, in response to existential conflicts.

These various influences and aspects of the tradition of poetic witness echo across our collective, global moment, indeed – into which, intentionally or otherwise, the American MAGA wing also reflects a fragment of this “mud glass,” with its violently anti-democratic election denialism and outrage at the fading of the Lost Cause mythologies, openly longing for a time when “folks” put on their Sunday best to attend the festive town lynchings. It’s a longing after the greatness of supremacist idealisms refracted through American essentialism in a country with an ever more diverse population, as resistant to a new normalization as Hamas, a new normalization that is imminently approaching.

It exists everywhere, this fascistic impulse, as much as the States has often led the way in legalizing hatred. This becomes one of the volume’s central questions. Humanity, riven with these contradictions, this willingness to sacrifice others on the altar of one more pure, more preferred community or another, sits perfectly balanced, unmoving in its formal embrace of its own spectral discontinuity, a dilemma articulated well in this excerpt from Kateryn Kalytko’s poem He Writes:

Mother, you haven’t sent me a single photograph

so I almost forgot what your face looks like.

you’ll cry, I know, I have caused you distress

but each trouble is just a speck of blood on a Sunday dress.

Life is a house on the side of the road,

old-world style, like our peasant house, divided into two parts.

in one, they wash a dead man’s body and weep.

in the other, they dress a bride,

Mother, I want you to have a dream in which I come

and sit in the part with more light.

Like what you’re reading? Consider donating a few dollars to our writer’s fund and help us keep publishing every Monday.