FICTION: “Kids,” by Tom Roth

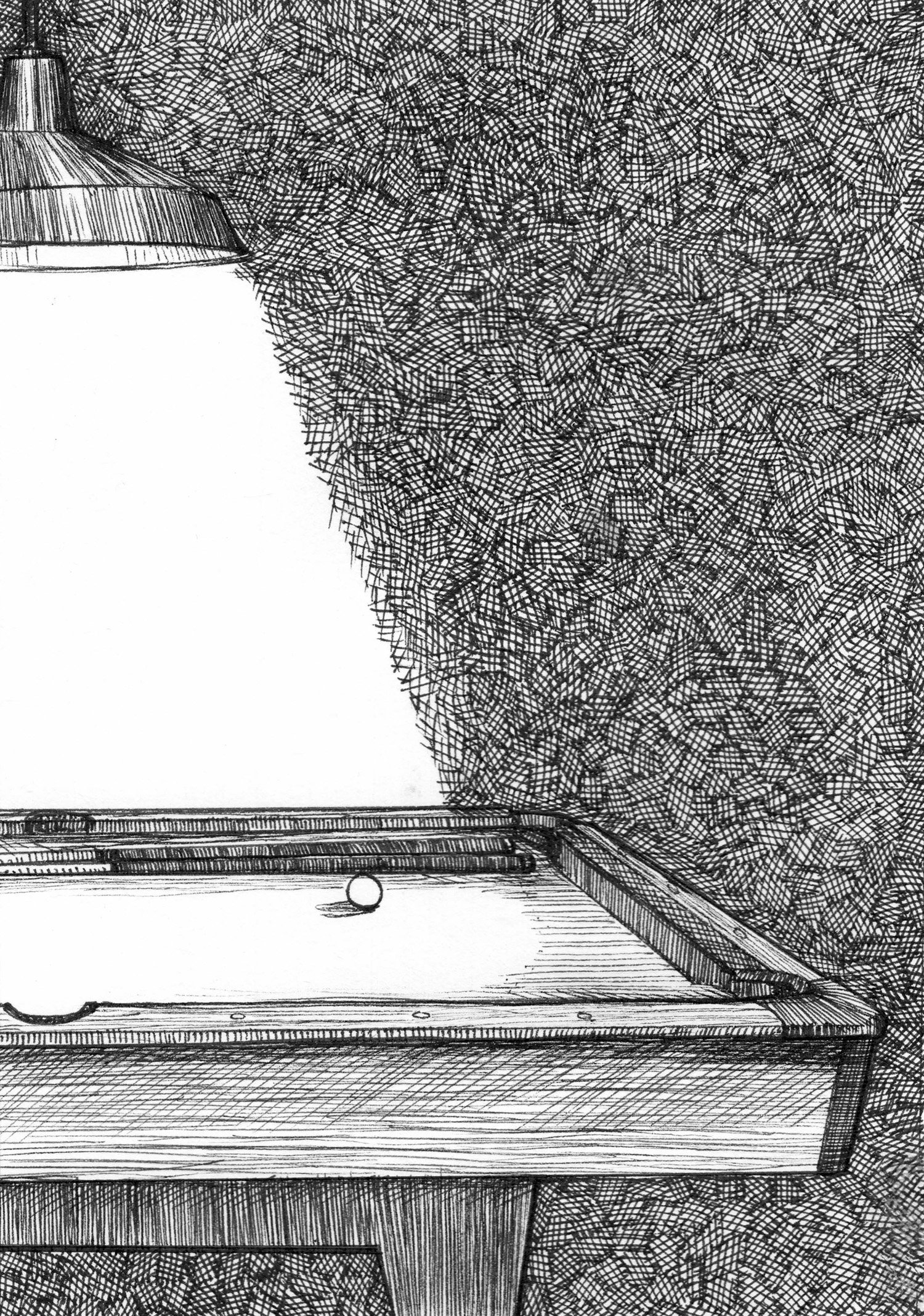

Illustration by Maura Walsh / Black Nail Studio.

FICTION

Kids

By Tom Roth

Welcome to baby-land, the best spot in town for having kids. Almost everybody in the neighborhood had one. Here cried the future of Glenwood, Ohio, where children never had to dream about tidy sidewalks and friendly cul-de-sacs and a nice new house with a puppy in the yard. They already had it, and their own babies would have it too.

Just look at the one across the street. A baby boy on his grandfather’s lap. His tiny hands steering the wheel of a Mustang convertible. In the driveway, his parents vroomed like happy idiots.

For a second, I thought of my mother serving beers at The Buck back home in Lewiston, Pennsylvania. Did that shithole survive? I could still hear the clack of the pool table, still see Mom behind the bar, even if she wasn’t anymore, even if I hadn’t been back in almost ten years.

Anyway, I liked babies. I wanted my own, too, but it was the people with the babies around here who I didn’t like. The ones with home theaters and barrooms and beach houses. The parents who emailed me arguing that dodgeball was “unsafe and outdated” for a middle school gym class. I showed Nate the email in the teacher’s lounge one Friday. Somebody brought in donuts. I grabbed a caramel cream-stick.

“Split this with me,” I said.

“Ava, I just had one.”

“Suck it down, you pretty bitch.”

“Now if I said that to you,” he said.

I sliced the sucker and handed one half and sat beside him to show the email on my laptop. Our knees touched. He took a bite of the donut while he read. I liked the silence of the room’s cabinets and tables, his quiet eating, the way he said my name earlier. I wanted my hand in his long dark hair.

“So soft,” he said. “But it’s always been like that around here.”

“Glenwood,” I said.

“Fucking Glenwood.”

“So how pumped are you for the tour tonight?” I said.

“Oh, I couldn’t sleep last night I was so excited.”

He swallowed a bite, smiling.

“Shut up,” I laughed.

“Can’t wait to see it.”

“Bring Katie, too. We wanna meet her.”

He looked at my paper plate. I hadn’t touched my end of the donut yet.

“You think?”

“Yeah.” I picked up my end. “She seems sweet.”

Flat. No hills in this part of Ohio, northeast, near Akron. Long planes of trees and farmlands dwindled between great stretches of suburbs and shopping centers. All of it level, zero change in elevation. Driving got old. Back home, Lewiston’s roads winded through steep woods. Fast curves. Narrow backroads. No intersections, no roundabouts. Never predictable.

I hadn’t been home because my parents died a while ago. Breast cancer took my mom when I was in high school, and my dad suffered a stroke just before I met my husband Dominic at Ohio State. Child of dead parents. Call me Harry Potter, Ponyboy, or one of the Baudelaire siblings. Never thought all those books and shows would be my fate. A cheap way for someone to feel sorry: poor girl, her parents are dead.

Jokes aside, sometimes in the middle of the school day, I’d think of Lewiston, and it made my throat warm up, made my eyes fall on nothing. I’d see myself there again, driving up a hill. The gym class gone, submerged behind a daze, and the kids would know it, too, how I had fallen into some trance.

“Mrs. Campano?” they’d say to snap me out of it.

Dominic and I bought a place in 2015, a few years after our wedding. Every tall brick house had the same features except for the gables and roofs. Cookie cutter. Too clean, too new. Homes so similar I nearly walked into the wrong house our first week in the neighborhood.

He was shooting hoops in the driveway when I got home. He was tall and athletic enough that he could sometimes dunk, and his looks resembled Nate’s, only his hair was short and neat and somewhat receded now that he was almost thirty.

“Round of Horse,” Dominic said. “Right now.”

“You sure you wanna lose again?”

Games meant a lot to us. We both played sports in high school. The first time we met was after a basketball game our freshman year of college in Columbus. Our first months together involved long hikes, biking, kayaking, beers after a run. I thought it made us different from other people—everyone else busy with campus bullshit like classes and Greek life.

“If I win,” Dominic said, “then we try before they get here.”

“After a game?”

“We got time for a shower and a quickie.” He passed me the ball. “Deal?”

Now that we had a house, he wanted a family, and I did, too, until I’d get to looking around, though. Perfect shade trees along the sidewalks. Playhouses in backyards. Caution signs: children at play. Down the road, a maintenance crew was hauling up heavy tarps of fallen leaves into a truck. A cold October sunset had fallen behind the houses and treetops. That Mustang across the street still shined in the shadow of the house. If my dad was here, he’d just shake his head and say, “Must be nice.” When it came to having kids, I kept thinking, Here? Here?

“Deal,” I said.

One picture of my parents could sum up their lives.

They’re at a pool table in The Buck. My father leans for a shot, his broad arms on the edge of the table. At first, his face looks hard and tough, but the more I study it, I realize it’s kind of numb, distant. He is somewhere else, and he knows he’s going to miss, but he’s too tired to care. In three months, after I’m born in 1985, the steel mill will close, and he will have to work at the bar with my mom before finding a job on the highway.

Mom stands on the other side of the table, watching him, a pool stick in front of her bulging stomach. Her hands are folded, like she is praying. This bar will own so much of her time, even her nights off. She wishes it was her shot. She’d have a better chance to make it, but she knows not to say this because it will hurt him, and they both still love each other enough to share a game of pool.

Katie just loved the kitchen floor—such nice wood! I wished she hadn’t said wood.

“That’s because it’s not wood,” Dominic said during the house tour. “It’s bamboo.” Bamboo. Now came his spiel. “It’s durable, pest resistant, and easy maintenance. Even environmentally friendly.”

“You sound like a fucking ad,” Nate said.

“Stop it,” Katie said. “It’s interesting.”

“Literally,” Dominic said, “you are such an asshole sometimes.”

“Literally?” Nate said. He looked at me. “Literally.”

“Yes,” Dominic said. “Literally.”

“Jesus, Dom,” I laughed. “You’re digging yourself a deeper hole.”

“What?” Dominic said. “All I’m saying is that he’s an asshole. Even now, when I’m showing my house.”

“Calm down,” Nate said. “It’s a joke.”

“Well, it’s my house,” Dominic said, then looked at me. “Our house.”

My husband had always been an easy target for us. In college, Nate and I made him our piñata. We beat the hell out of anything he said until his speech was empty and broken. The stuff he said proved he never had a strong grasp on anything beyond account analysis and fantasy football. What a Whac-A-Mole game. Anytime he opened his mouth—WHACK. But, in all honesty, I liked that side of Dominic. His misunderstandings. His innocence. It wasn’t only that he could make me laugh. I could trust him, and I knew he knew I always did, because his heart still held a kind of simplicity, like childhood, that separated him from others.

But ever since we moved into the house, Dominic had voiced more and more of his thoughts with an effort to prove, to show he was more than the joke of our triangle. Sometimes, I’d look at him speaking in front of others. Take me seriously, he seemed to say beneath it all. I’d wonder what happened to the quiet, childlike face I first met. A face I wanted for myself. For only me to know what he thought and felt. But now his thoughts were popping up for anyone, and there were too many to whack away, and most of what he said seemed more for show than self.

“Be nice,” Katie said to Nate. “You know what’s weird?” She turned to me. “Besides the hair, they sort of look related, don’t they? Kinda like brothers.”

“I could see that,” Dominic said. He wrapped his arm around Nate’s shoulders. “I mean, we were always together growing up, and Nate visited me and Ava in Columbus all the time.” Nate went to college in Cleveland, but he came down almost every weekend. “It makes sense.” Dominic balled his hand into a fist and deepened his voice. “We’re blood brothers.”

“If you say so,” Nate said. He moved out from Dominic’s arm. “Brother.”

The evening went like most nights in Glenwood. Drinks, dinner, barhopping. At the end, drunk and dumb, we fooled around on a dance floor. A good crowd tangled, grinded together, and we stood on the outside at a table, waiting for Dominic. The crowd glowed, their wrists and arms and necks radiating with colorful bracelets. They looked young, really young. Boys wearing snapbacks. Girls showing more skin than me. None of us wore any bracelets.

“Lot of babies in here,” I said.

“I was just thinking that,” Nate said.

“What?!” Katie shouted over the music. She was a ginger. Chatty and perky. Cheerleader smiles. I could already tell she was nothing more to Nate than just some chick. He repeated what I said, then Dominic arrived with plastic cups.

“Vegas bombs, bitches!” he said.

“How original,” Nate said.

“Shut up and drink.”

“Ava says we’re too old for this place,” Katie said.

“What—no come on,” Dominic said. “I mean, maybe a little.”

“Almost thirty,” I said.

“That’s not old,” he argued.

“Wasn’t that long ago we were over there,” I said, pointing to the crowd. “Pretty soon, we won’t even be here,” I said, my finger on the table.

“Damn, don’t say that,” Nate said. “Your life just goes, doesn’t it?”

“Would you shut up and drink already?” Dominic said again. We downed the bombs. I almost puked. “Let’s go,” he said. At first, I thought he meant to leave. Instead, he wanted to dance, and he had bent down to grab something off the floor. A blue bracelet. He slid it over my wrist. “Come on.”

My family had a pool table. It was in the concrete basement, among boxes and cobwebs. At night, after my homework, I’d find Dad down there. His stick aimed at the cueball. A light bulb swaying over him. Storage in the way. Blackened brick walls against your elbows.

“I’ll rack ‘em,” he’d say at the other end of the table, the balls assembled into the triangle. “You crack ‘em.”

He loved a good spread. “Look up there,” he’d say, pointing, his voice quiet like in church. Every game offered a constellation. A way to recognize where to look, how to shoot, which ball to sink. He never left a table unfinished. Bad luck, according to him. A lot of times, even after he had decided on a shot, he’d go still and stand there in a kind of trance, his eyes on the table, the balls whispering to him. “See this over here?”

I lost almost every game. Threw tantrums about it. Cries. Flinging arms. Stamps up the stairs. No way to act, he’d lecture, even if Mom backed me up. He was too hard on me, she’d argue. That pool table got all his attention. Didn’t he have anything better to do than waste time in the basement, playing silly games of pool all night?

“Wanna bowl?” I said.

Nate stopped by my classroom—the gym—a week after he and Katie saw our house. Today’s activity was bowling. Sets of plastic pins stood along one side of the court. Rubber balls on the other side. I’d handout candy to kids with the highest scores.

“I should get going,” Nate said.

“Where do you have to be?” I said.

He was just a tutor in the school, someone who helped in classrooms when he wasn’t working one-on-one with a student. After college, Nate drifted for some time. He started out in business shit, but dropped all of that to move to Florida, where he worked at a guitar shop and played at small gigs. He was good at guitar, could sing, too. But this tutor position he had gotten might have been the first job he actually cared about, and he considered getting a master’s in education. So maybe just a tutor was a bad way to put it.

“If I win, you buy a round of drinks,” I said. “If you win, I buy.”

We bowled. We’d walk down the lane and reset the pins, the two of us kneeling next to each other. His hair would fall over his face when he’d pick up a pin. I thought of pulling him over me, the pins falling around us.

A part of me always wished I had met him first. Unlike Dominic, Nate was unafraid to speak his thoughts or show what he meant without having to prove, without having to be more than himself, and what he said was always what you needed to hear, not just what you wanted. And if Nate was the one who had found me in Columbus after I buried my dad, then maybe I wouldn’t be here, in Glenwood, turning into someone with bamboo floors and too many televisions. Maybe I’d be somewhere else, in a city with Nate, and I’d hear his guitar at night. Or maybe I’d be back home in Lewiston, without Nate or Dominic, and I wouldn’t have to wonder what mom might say if she saw me now.

“Never settle,” Mom once said.

I was twelve, tired from my first sleepover. We were in the car. Mom took backroads through the hills to get home. Autumn morning, yellow and orange leaves, gray and cold. She was driving too fast, swerving too close to the drops.

“Mom,” I said.

Saturdays meant double-shifts at The Buck. Twelve hours of serving beer and Jim Beam. Noon to midnight. A crowd of men watching football. On those nights, I’d lay in bed and try to imagine her there, but I could only see her driving home in the dark. Quick bends around the foothills. Her hands tight on the wheel, as always, and her eyes forward. She’d make the car fly, if she could. She’d fly out in the night and look down at the hills that towered over her all this time, and she’d point her headlights to some place on the other side.

The road curved toward another drop.

“Please slow down,” I said.

“You hear me?” she said. Her hair was wet from a shower. A hand left the wheel and covered her mouth. I said her name, and she closed her eyes. We sped up a hill. “I said do you hear me?”

I tried to tell her yes.

The main room of Nate’s apartment had white walls and an empty brick fireplace. Guitars hung on one wall—an electric between two acoustics. We sat on the couch and sipped beer. It was after work, a Thursday. Outside the window, leaves twirled and spun in the wind, their colors lit in sunlight. I felt cozy, my feet and knees curled up on the couch. We talked about work for a while.

“Are you happy?” I asked him.

“What do you mean?”

“With tutoring,” I said. “Once you finish school and start teaching, you’ll be ready to settle down, you know?

“What you said last weekend,” he said. “About those college kids at the bar. All those babies.” He smiled. “You’re right, though. We’re getting oldish, and it got me thinking, like, what’ve I been doing all this time? Like I’ve already let too much of my life go by.”

“I feel like that, too.”

We moved into each other, and he climbed over me. For a while, we just lay and kissed, tangled together like kids on the couch, and later on, in bed, he told me he wished this had happened a long time ago.

I once found my dad asleep with his eyes open. This was the same night I learned about Mom’s breast cancer, after she had driven me home from the sleepover, her hair wet, her eyes shut. “Never settle,” she kept saying.

I couldn’t sleep, and I heard Dad in the basement, playing pool. He took his time between shots. A long silence before the next clack. I looked up at the dark and heard him playing and turned in bed. Not many balls found holes. No loud thuds. No good rolls down the table.

He stopped playing some time past midnight and didn’t come up. I waited for the next shot, for his steps through the house.

I found him sitting in the only chair. His head rested within the corner of the wall, and his eyes stared at the balls on the table, his face somewhat disturbed, like there were bugs in the house. He still held a pool stick between his legs. He looked dead, and when I realized he had only fallen asleep, I wondered if he should’ve been, because death seemed more a mercy than sleep.

November arrived in a veil. Fog clouded the mornings and thickened the sky in the afternoons. Mist floated like torn dresses instead of fine curtains and blankets above the hills in Lewiston. Our neighbors bundled up their babies. Their daily walks down the street had lessened— too cold, too dark—and the lack of sunlight turned their faces pale.

“A pool table?” Dominic said.

I said yeah, that it’d be a good addition to the basement, and he nodded. He was at the window by the front door, looking at the fog on our street, a cup of coffee in his hand. It was a Saturday, and we had nothing to do, the day already over.

That morning, I found the picture of my parents at the pool table, their lives summed up in one moment. Other than this and my memory, I never understood in full why they were unhappy. No matter how many times I studied it, no matter how many times I replayed a moment in my head, no answer surfaced, and the thought of it all made me feel inflated, a balloon ready to pop.

How were you supposed to fill your life with someone? “Your life just goes, doesn’t it?” Nate had said. All these tiny increments add and add by the moment, but to what in the end? And I tried to see me playing pool with Dominic. Tried to hear the clacks and breaks and rolls. To feel the weight of the white cueball in my hand. To know which shot to take and where to go next.

Nate and I got together only a few other times after that day at his place. What we did was never the type of thing you’d hear about or what you might’ve seen in bad movies. No hot juicy affair. No doomed lovers. No cuck seeing his wife in a good hard fuck sesh with his longtime buddy. Oh, what betrayal! What scandal! How could they?!

No. Our end began with what Nate said after our last time together.

“I just think this should’ve happened a long time ago,” he said.

“I do, too, but you’ve already said that,” I said, my hand in his hair. “We have this now.”

“Doesn’t it feel like we’ve missed our chance, though?” He pulled my hand away. I still wanted it there. “It’s like we’re trying to start something that’s been gone a while. I mean, what are we gonna do—run away together and begin a new life?”

I said I didn’t know.

“Right,” he said. “It’s already gone, you see what I mean?”

I said I did. But I wanted to tell him this was our chance, this was now, even if it was too late. Gone. What a bad word. It made me think of my mom driving up a dark hill, ready to fly.

“I’m pregnant,” I said.

We were playing a game of pool in the basement. The table got here a couple of weeks before Thanksgiving break. It gave us something to do when we had no plans. I liked watching Dominic bend over for a shot and look at me after making one.

“You are?” he said. “Really?”

At first, I felt it belonged to Nate, and I almost said that to Dominic, but the moment I looked at him I could make out my dad’s face in his. The way he aimed. His eyes fixed on the cueball. How he looked up after his shot. There was a night in the summer, just before I moved to Columbus, when I said to Dad I was afraid of college.

“You are?” Dad said. He would die that autumn, and I would meet Dominic. “Really?”

All this had happened, I could feel it, I had lived through it, I’d been here before.

I said yes, and it was his, no matter what I felt.

Dominic dropped the pool stick on the table and hugged me. I faced the spread of balls. Only the white one moved among the others. It spun and spun upon that flat green, and then settled.

Tom Roth teaches creative writing at a middle school in Cincinnati, Ohio. His most recent publications are in The Baltimore Review, On the Run, and Outlook Springs. He earned an MFA from Chatham University. He recently finished a draft of a novel titled Silva, Ohio. He has a publication forthcoming in Allium.

Like what you’re reading? Consider donating a few dollars to our writer’s fund and help us keep publishing every Monday.