REVIEW: Frederick Kiesler’s “Vision Machines” at the Graham Foundation

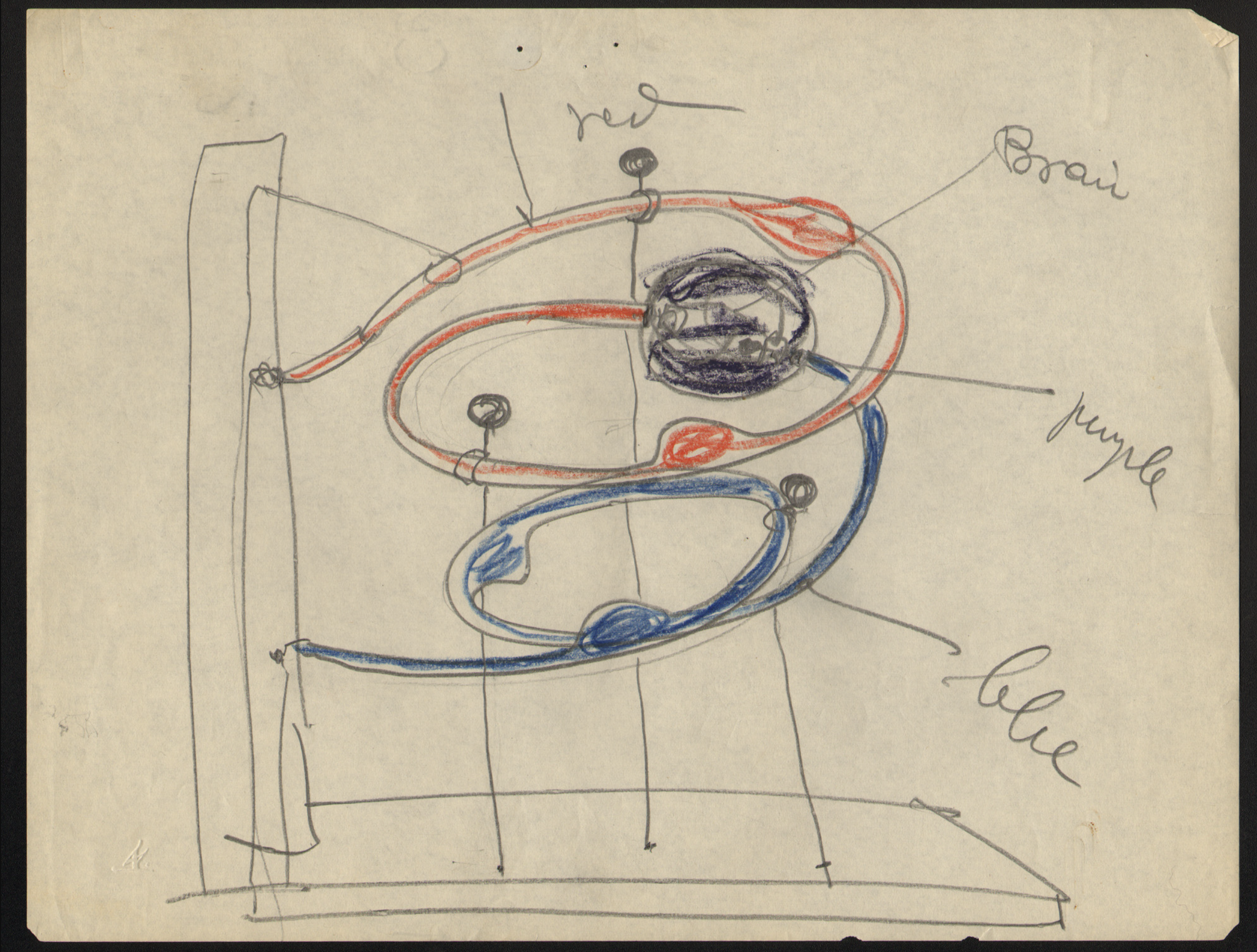

Frederick Kiesler, "Detail study of the Vision Machine (Tubes/Biolite)," 1938. Pencil on paper, 8.46 x 11 in (21.5 x 28 cm). Copyright Austrian Frederick and Lillian Kiesler Private Foundation, Vienna

REVIEW

Frederick Kiesler’s Vision Machines

Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts

Madlener House, 4 West Burton Place,

Chicago, Illinois 60610

October 23, 2024–March 15, 2025

By David Sundry

Though the reputation of Frederick Kiesler has to some degree been resuscitated over the last few decades, he is still perceived as an elusive figure and his career a fly-over realm between (or across) previous and current disciplines.

As an architect Kiesler’s only projects that are generally still discussed are the Art of This Century Gallery for Peggy Guggenheim in 1942 and his continuously evolving Endless House. He is still portrayed as the “greatest non-building architect of our time” a somewhat backhanded compliment by Philip Johnson and reinforced in 1960 by Ada Louise Huxtable the legendary New York Times architecture critic. In addition Huxtable also accused Kiesler’s concept of architecture as being insufficiently architectural and amounted to a kind of “unpardonable reversal of legitimate architectural procedures.”

View of "Frederick Kiesler: Vision Machines," Graham Foundation, Chicago, 2024. Photo: Nathan Keay

Paradoxically, Kiesler, though marginalized, was also largely celebrated in his time. First, as a member of the avant-garde (he joined the de Stijl movement in 1923), next as a collaborator with Marcel Duchamp and Max Ernst and finally Kiesler was included in at least eight exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art between 1932 and his death in 1965. However, his reputation faltered and it was not until the late 1980’s in the Postmodern era that Kiesler’s interdisciplinary quality (or multi-dimensionality) was again critically evaluated and now positioned “inside” a theoretical/historical discussion. Kiesler would most likely have resisted this characterization as Postmodern practitioner as he believed his career constituted a continuous multi-faceted investigation and development of an idea. Kiesler sought a cross-disciplinary realization not as an evasion of conventional disciplines but as a means to anchor his practice in real procedures that were not wholly available within any current discipline at that time. Again, his practice was not one of avoidance or a failure to solve the problems posed within an existing discipline, but to necessarily cross boundaries in order to more accurately frame an emerging question or problem. It is just this procedure or questioning that somehow appears as fragmentary or elusive but it was his aim to safeguard artistic statements from ideological limitation and to ground these practices in some kind of broader method not unlike that of science. With this strategy, Kiesler solidified his modernist approach and sought to keep some of the broader political limitations of the avant-garde at arms length and, hopefully, realize his goals within institutions, industry and the public at large.

The ongoing exhibition at the Graham Foundation, “Frederick Kiesler: Vision Machines,” through March 15 is curated by Mark Wasiuta and focuses on a specific aspect of Kiesler’s broad experimental practice—his Mobile Home Library and Vision Machine. First, let me state that this exhibition is a necessary tonic to set the record straight about the practice approach of Frederick Kiesler, the what he does and how he does it, and gives valuable insight into how an interdisciplinary practice actually works.

Frederick Kiesler, "Mobile Home Library as represented in the Correalism Manifesto," 1947. Copyright Austrian Frederick and Lillian Kiesler Private Foundation, Vienna

The exhibition is anchored by two exceptional recent fabrications of Kiesler’s prototypes. First, a rotating viewing or informational display system that contains eight vitrines of drawings, documents and diagrams of the investigations from the Laboratory of Design Correlation (LDC), a course Kiesler developed and taught from 1937-1941 at Columbia University. Second, the Mobile Home Library, another project from the LDC. It should be noted that this is the first ever complete full scale fabrication of this prototype. The faithfully executed fabrications both anchor and provide material connection to the visionary investigations of the LDC and, in general, Kiesler’s project and practice approach. This is a good time to emphasize that, I believe, Kiesler is above all an architect and designer — a problem solver. Design is a human activity that, at its core, imaginatively reconceives ideas in the service of the actual construction of objects or artifacts and point towards practical possibilities — the pivot of theory towards human betterment and possibility.

A good deal of research at the LDC was guided by Kiesler’s theory of “Correalism”, which was a practice approach that incorporated a number of his non-disciplinary investigations in the conceptualization of a problem. As artist, Kiesler incorporated elements of his earlier avant-garde explorations with Constructivism and de Stijl, but his restless inquiry soon moved beyond architectural and design engagements with space and environment. It seemed Kiesler recognized the necessity to broaden his approach to encompass energy exchange — mechanical, scientific, cosmic and corporeal — and soon thereafter, a range of subcategories that culminated in his conception of “bio-technique” which was a biologically oriented design process meant to foster human health.

With the aim of reconceptualizing everyday objects, these investigations at the LDC included analysis of activities and work processes, cycle-time studies, respiration measurement, and fatigue reduction amongst others. This cross-disciplinary interactivity between psychology, physiology and biology aimed at not only an “active object” but an activation of objects in space and environment through human perception and engagement and led to Kiesler’s final project with the LDC, the Vision Machine. With this project Kiesler hoped to reveal the “flow of sight” in order to demonstrate vision as a “creative action”, an activated energy exchange of external impulses, optical mechanics and the resulting disconnected hallucinations, dream-images and mind visualizations that are human vision and perception.

View of "Frederick Kiesler: Vision Machines," Graham Foundation, Chicago, 2024. Photo: Nathan Keay

Instead of claims and position statements advocating Kiesler as a one-man “canon of progressive thought” (Huxtable), this exhibition fabricates, makes material, and brings forth the machined industrial connection that this phase of Kiesler’s work advocated. In addition, it displays the work in the original sense of the word as “to unfold” or “to spread out” or to make conspicuous. Earlier in his career, Kiesler experimented in exhibition design and he was interested in the concept of how ideas were brought forward and therefore able to influence process and outcome. The curation of this show achieves this goal. We witness his reaching, his muddling, his brilliant fumbling forward to an idea outside the scope of correct procedure and, indeed, the time itself. We see his proposed partnerships with institutions and industry, and his straightforward incorporation of science as a means of investigation (not as ideology) and his aim to negotiate with the demands of the avant-garde. A Kiesler aphorism provides some outline to his thinking — “Form does not follow function. Function follows vision. Vision follows reality.” Huxtable is misguided in her criticism that Kiesler’s method is both an evasion and reversal of architectural procedures. Kiesler is advocating for something beyond mere architectural history and procedure. He is beginning to envision something like sculpture/science thinking in which function sustains form, the flow of sight is form, almost like the refashioning of the previous disciplines into something like an organ — whole, all together, one.

In an age of the institutional establishment of inter-disciplinary practices, and its shallow fetishization as a body of knowledge that can be “taught” to willing 18-year-olds who are still unaware of what actually constitutes a discipline, Kiesler’s truly innovative shake up of categories and their boundaries was driven not by a lack of ideas within a form but a realization that a correct formulation of a problem lay elsewhere. It is not something that is “taught” but acquired after long and involved commitment and failure within an existing approach.

David Sundry is Architecture Editor of Bridge.

Like what you’re reading? Consider donating a few dollars to our writer’s fund and help us keep publishing every Monday.