FICTION: “Waiting for My Prince Who is a Clever Queen” by Amy Bobeda

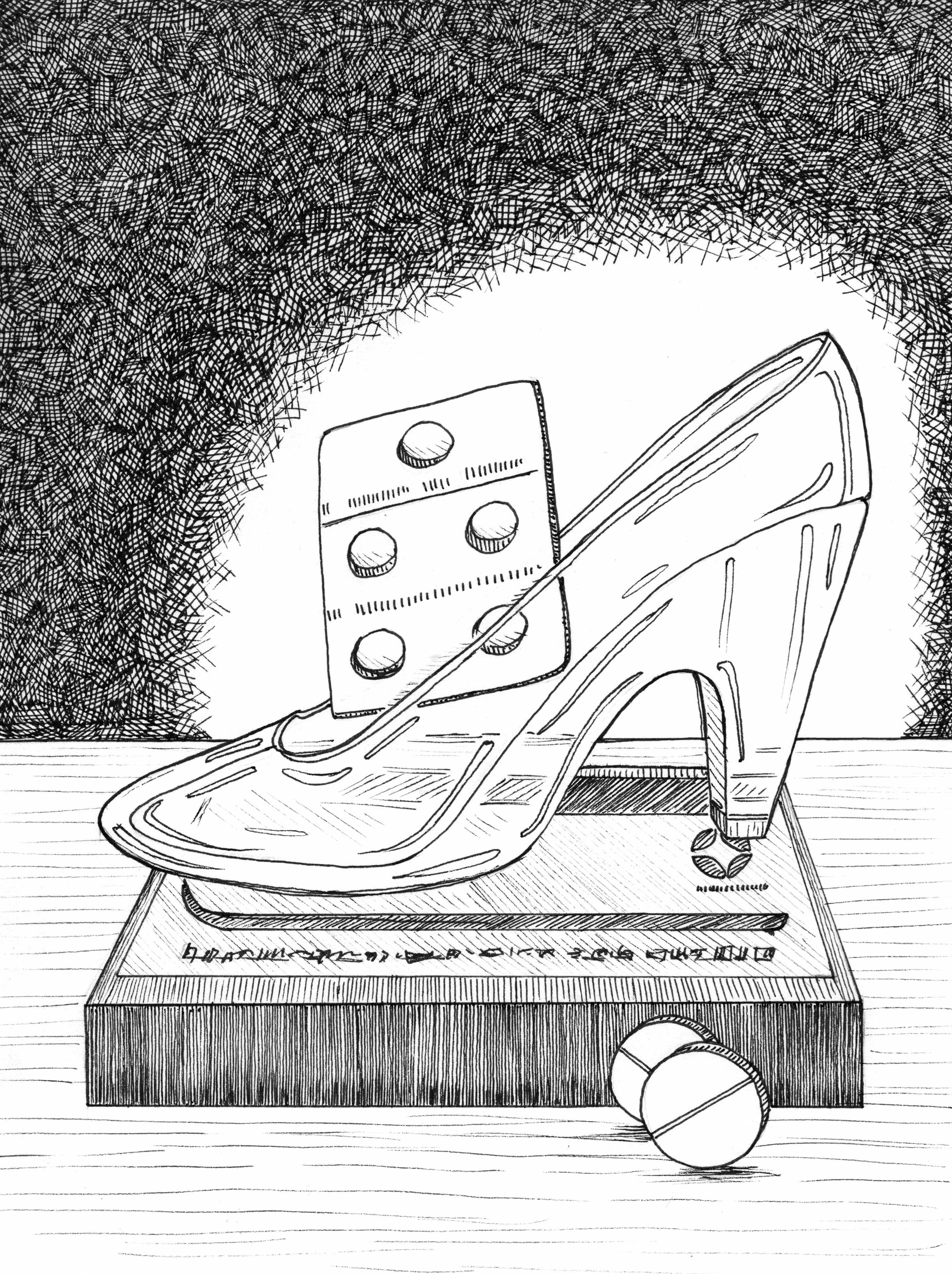

Illustration by Maura Walsh / Black Nail Studio.

FICTION

Waiting for my Prince Who is a Clever Queen

By Amy Bobeda

I am grading assignments that are 68 days late. I am grading assignments that are so late they are no longer assignments. They are tufts of fur the spirit of the assignment ate and coughed up 67 days later. They are matted and fuzzy and one is a little bit moldy. “The person who makes you wait is the one who holds the power,” a friend says in a women’s circle. She learned this lesson about power and waiting from Betty Draper on an old episode of Mad Men the night before the courts announce they may reach a ruling on the legality of mifepristone or they may extend the ruling deadline. They may strike their gavels or allow them to float midair a while longer.

In The Peasant’s Wise Daughter, a daughter finds a golden mortar buried in land her father begged off the king. The daughter tells her father—“Don’t you dare give that to the king because he’ll want the pestle too.” Her father doesn’t listen and the king sends him to prison. The dueling orders over mifepristone—legal—illegal—unsafe—FDA approved––guarantee the case a visit to the Supreme Court to be ruled by the 9 kings of legalese. Once in prison, the peasant laments to the king that he should have trusted his daughter. Because kings love exploiting the minds and bodies of clever young women by limiting abortion access and birth control options, the king gives the peasant’s daughter a riddle: come to the castle neither naked nor clothed, neither walking nor riding, neither on the road nor off it. If she guesses the riddle, he will marry her. The court does not make laws, they only interpret them and in turn new laws are made like riddles.

When the Biden administration stepped in to pause the appellate court ruling to limit access to abortion medication, it was framed as having “sweeping consequences” not just for abortion seekers but the larger pharmaceutical industry—a 1.4 trillion-dollar arm of American Capitalism. When the kingdom begins to question the safety of one medication—others follow. Thousands of pills, millions of people lose life-saving medicines.

The clever daughter wraps herself in a fishing net. She ties it to the tail of a donkey and is dragged to the castle with only her toe touching the ground. In many menarcheal rites, the initiate exists in a limonoid space. They cannot touch the ground, or let sunlight fall upon them. They are a riddle, a gavel caught in mid-air streaming blood. When the king sees the girl, he’s ecstatic. He sets her father free and marries her immediately.

I think about fairytales of waiting: Sleeping Beauty, Snow White, all those princesses on their menarcheal rites. And the reverse—waiting for the clock to run out at the ball, waiting for the man to spin straw into gold, waiting in the forest for 7 years to grow back your hands. Waiting for the last assignments of the semester, like half eaten breadcrumbs, waiting for dinner to become a wolf in old women’s clothing.

When time passes in a fairytale, no one waits. It just happens. Eventually, a mare gives birth to a foal that runs away and lies down under an ox. The king decrees the owner of the ox is now the owner of the foal. The queen rolls her eyes and tells the peasant to take a fishing net and pretend to fish on dry land. When I am not grading or reading about mifaprestone and fairytale waiting, I am running, which is also a kind of waiting. Waiting for calories to burn. Waiting for anger and stress and petty arguments to pass to the rhythm of Hamilton. Waiting for blisters to form. In the park, a man practices fly fishing, flicking his wrist towards a hula hoop sinking into the spring grass. His lure glitters.

When the king says, “you cannot fish on dry land.” The man replies, “it’s no crazier than an ox giving birth to a foal.” When the king realizes this is his own wife’s advice, he sends her back to her father. “Before you go, you can take the one thing you cherish most from the castle.” Even kings have the capacity to be kind and horrible at the same time. The clever queen slips her husband a sleeping pill before it is outlawed by the Supreme Court. When he wakes it’s as if no time has passed.

Only the queen waits. Next to her father in the home on land begged from the king, the king opens his eyes to find that he is what she cherishes most in the castle because in their kingdom no one is waiting for answers on abortion access wrapped in fishing nets waiting for carp on dry land.

Amy Bobeda holds an MFA from the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics where she serves as the Director of the Naropa Writing Center. She sometimes teaches writing pedagogy and process-based art. She's the founder of Wisdom Body Collective, a process-based artist collective and small press. She's the author and illustrator of Red Memory (FlowerSong Press) mi sin manitos (Ethel Press) and has a forthcoming book from Spuyten Duyvil. Her work has been featured in Columbia Review, Ecotheo Review, Denver Quarterly, and elsewhere. She's also a retired cosmetologist and costume designer who loves reclaiming and refashioning fiber arts. Raised on the Amah Mutsun land of the Pajaro Valley by two ceramicists she is often found running, walking, and following birds in landlocked places.

Like what you’re reading? Consider donating a few dollars to our writer’s fund and help us keep publishing every Monday.