REVIEW: Ruben Quesada, "Brutal Companion"

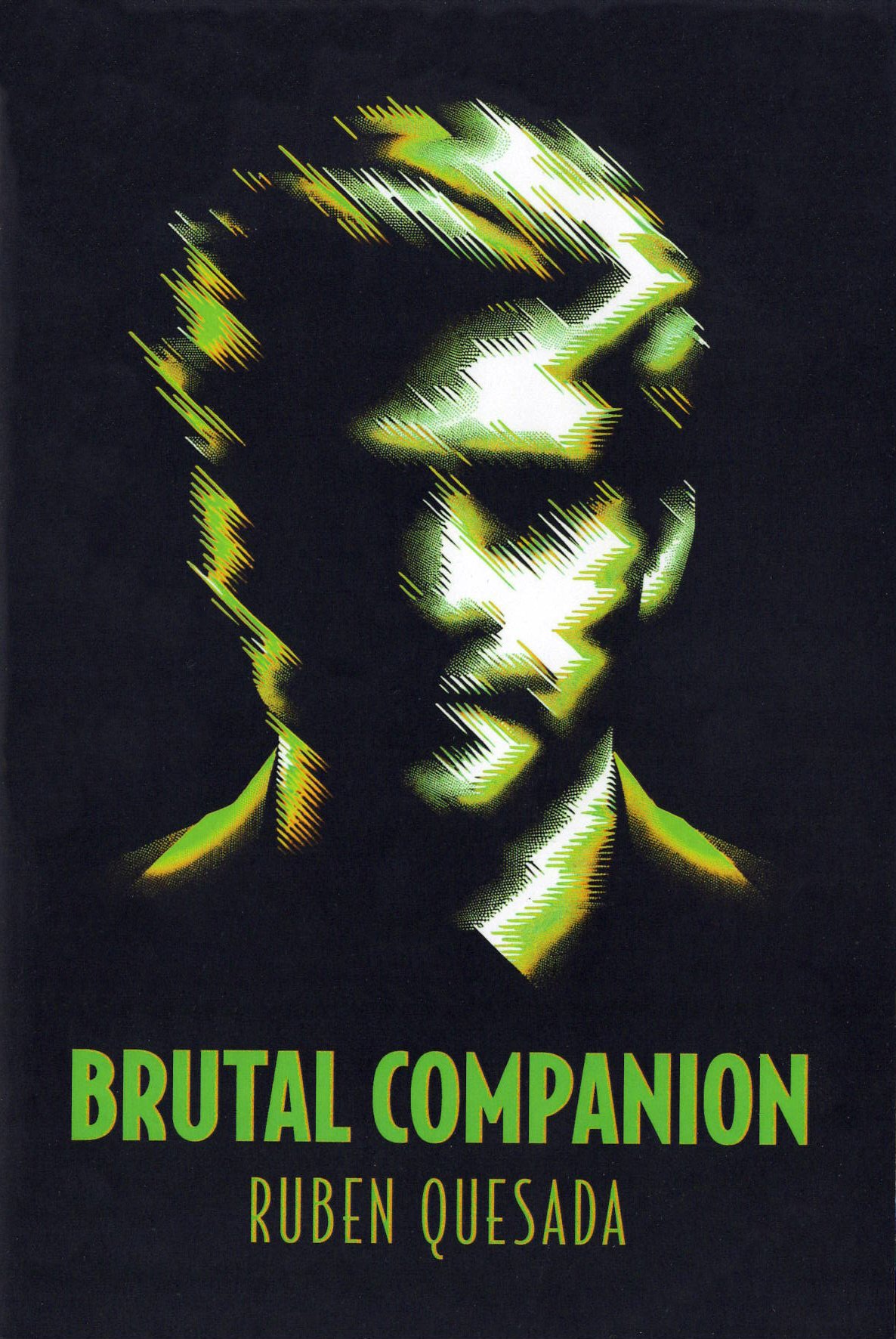

Cover, Brutal Companion by Ruben Quesada. Image Courtesy Barrow Street Books.

REVIEW

Brutal Companion

By Ruben Quesada

Paperback ($18)

Barrow Street Press

By Michael Workman

Brutal Companion, Ruben Quesada’s latest collection (Barrow Street Press), delves into mortality, myth, and queerness with striking intimacy. A former Angeleno and founder of the Latinx Writers Caucus, Quesada explores themes of cultural displacement, intimacy, and life’s fragility in a way that reaches out to readers like a whispered confession. Anchored in his past work across Revelations (2018) and Next Extinct Mammal (2011), this newest collection often returns to explore themes of cultural displacement, intimacy, and the fragility of life. Reading these tenderly constructed verses, you can sense the sweat, the high, the sadness just on the other side of the page, reaching out to you.

This excellent, visionary and pulsatingly alive volume of Quesada’s work, a product of the Barrow Street Editors Prize, is heavy on all the above themes (delving as it does partly into his devastating 2016 HIV diagnosis), while also diving deep to interrogate memory, loss, damage and transformative personal experiences through the fractures of this diagnosis—and the serrate sting of it seen through a prism of time, aging and illness.

Take this passage from “House Fire:”

I am nine late on a Sunday. Next door,

the family returns from church to find

their six year old, his room aflame,melting

the curtains above their kitchen sink.

One of many passages in these poems that occasionally puncture the moment with apocalyptic imagery that comes in ways throughout the collection, both large and small, moments of near-mystical fracture for the poet, moments that invite the reader into the experience as a kind of pathfinding into the processes at work in Quesada’s poetics. This psychological, prismatic lensing occurs in part because of a history of self-medicating he details going back to his teenage years, inextricably intertwined with his love of books, reading, poetry. Take for instance, this passage from “Year of the Dragon:”

I stayed up all night

The first time at sixteen

After snorting amphetamines

Down the street from home

In Hollywood with a man

Who I’d visit when

I wanted to get high

Cigarette after cigarette

To talk about books

Before and after

Chasing the dragon

Until the sun rose

It’s a theme that recurs throughout the volume, often heartbreakingly so. At times, it offers moments of liberative relief or a sense of muddied distance from grief, as the pressures of the world and its pervasive bigotries press in—always just on the other side of the glass of a discomfiting reality. Sometimes, it’s the stories of friends and lovers, of tragedies compounded by a world steeped in brutality, excess, and oblivion.

It’s a theme that recurs throughout the volume, often heartbreakingly so, at times offering moments of liberative relief, or offering a sense of muddied distance from grief, given the pressures of the world and bigotries that seem to always be pressing in, always just on the other side of the glass of an discomfiting reality. Sometimes, it’s the stories of friends, lovers, of the tragedies compounded by a world full of brutality, excess and oblivion, drowning out the world and embracing oblivion, as when he writes in “SLC Punk:” “You told me about the time in Salt Lake City / where you spent a night in a sling, high on heroin, and a line / of married men waiting their turn to be inside you.” These narcotized passages, raw and unflinching, intensify Quesada’s moments of myth-making—the brilliance of sunlight and the depths of shadow, the oscillation between longing and transcendence. In “Angels In the Sun,” one of the many poems dedicated to other poets, writers and visual artists such as Carl Sandburg, Édouard Manet and Marc Chagall, this one “After JMW Turner,” he writes: "I would have waited alone / A thousand years for the coming of angels / to abandon this world for another."

One can almost see The Fighting Temeraire being hauled away into the sunset, its light a harbinger of loss and transformation. Parallels emerge in Quesada’s searing metaphysics, weaving together nature and its corrupted human version while grappling with faith, sin, and suffering. These frequent conjurations of angels and Christ imagery evoke the fraught relationship between these impulses and the reflections that follow.

How rich those years of yielding to impulse—for a poet or artist, these are as much born from the need to snuff out the pain of existence as from a silent, senseless devotion to truth, or perhaps a plot to see how the world reacts. (Hint: most respond the same.)

The alignment of these life investigations is a longing for a reality alive and loving despite it all, filled with moments of calm and respite, a willingness to embrace the full spectrum of success and strife, of loving as much as we can while awaiting the inevitable struggles such that they almost come to define Quesada as they do any of us, a dichotomy depicted here in such lines as:

Then came a heat—the world’s heat rose

To meet the body’s blood boil. This is

the will of the body. The body—splits

into atoms, faces yawn into skulls.

We sun. We become.

We become undone.

Working against the narrator’s hopes, this destruction—this subsummation into light, heat, and the end—becomes an entirely new experience of undoing. The repetition in these lines evokes the dissociated, dreamlike state of someone who will never arrive, forever circling their own unraveling. Is it this self, brutalized and fragmented, that remains our constant companion? The love found in fleeting interstices, moments on the nod, immersed in blinding embraces and heat—another iteration of the world layered over the old experiences of ourselves within it? Is it loss overcome, the lost recovered? Or all of the above? We’ll let Quesada have the last words, perhaps now imbued with the power of resurrection, in this passage from “A PÆN:”

To know what loss

is like, you must

lose everything,

you must lose

even yourself, you said.

I am alone.

Each night I lie

and learn

to sing

the dead back.

Michael Workman is Editor-in-chief of Bridge.

Like what you’re reading? Consider donating a few dollars to our writer’s fund and help us keep publishing every Monday.