REVIEW: With Mies, Negation is Enough: Michelangelo Sabatino, "The Edith Farnsworth House"

Cover, The Edith Farnsworth House by Michelangelo Sabatino. Image Courtesy Monacelli / Phaidon.

REVIEW

The Edith Farnsworth House

By Michelangelo Sabatino

Hardcover ($75)

Monacelli / Phaidon

By David Sundry

For nearly 75 years since its initial unveiling at the eponymous exhibition dedicated to him at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City in 1947, Mies van der Rohe’s “Fox River House” (as it was originally referred to) captured the attention of the world of architecture and the national press. Mired in mystery, metaphysics and controversy, Farnsworth House has been variously depicted as the pinnacle of the modern architect’s spiritual quest to capture the immaterial within the material or the hubristic flapping of architecture’s wax wings.

In 1945 Edith Farnsworth commissioned Mies to design and eventually construct a weekend country house located in Plano, a rural site along the Fox River west of Chicago. The Fox River was infamous for overflowing its banks each spring. Despite this fact, the client and architect, each interested in situating the house within the landscape and to engage a specimen black sugar maple sited the fireplace so that it “stands directly opposite” and that the “sitting area is framed by the fire and tree through which one looks out to the larger landscape and the Fox River.”

The Edith Farnsworth House with black sugar maple, photographed by Bill Hedrich, fall 1951. Image courtesy Phaidon / Monacelli.

Mies had long envisioned a residence or structure that would dissolve into the natural setting, a lens to observe every seasonal change. The crystalline box, a white-painted one-story glass-and-steel pavilion on eight supporting columns raised on a floating podium to offset the seasonal flooding still managed to fuse with a classical ideal - a modern machine temple in the landscape, a hovering plinth with vertical steel supports (columns) and a horizontal steel architrave. Its symmetrical and neutral indiscernible structure is enclosed with floor-to-ceiling glass on all four sides. The resulting volume is a fluid space with a free-standing core. No partition touches the exterior envelope. The pavilion is not an object in the landscape but a hermetic interior in alliance with its environs.

The Edith Farnsworth House is the latest publication by Michelangelo Sabatino, the Professor and Director of the PhD program in Architecture at the College of Architecture of IIT and a trained architect, preservationist and historian. It is a handsome monograph that helps to further position the cultural shift of our reception of the Edith Farnsworth House (officially renamed to include her first name on November 17, 2021) from private to public, from home to museum, and interestingly, as Sabatino notes, from architect-directed image to photography based in personal interaction and currently to a broadly experienced “site of encounter” through a flood of iPhone social media postings.

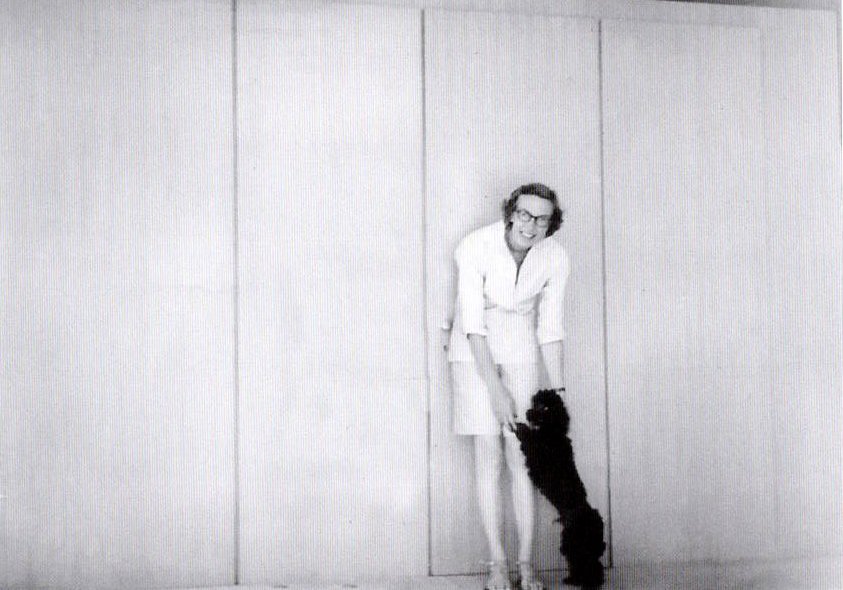

Above: Edith with Miss Amy inside the house against the primavera core, photographed by architect William E. Dunlap, c. 1951. Image courtesy Phaidon / Monacelli.

The book includes a number of essays including Dietrich Neumann’s overview of Mies’s stylistic and technical development and an in-depth exploration of the refined and costly detailing of the structure itself. Sabatino expands upon the influence of the Wright/Mies innovations and their reception in the Midwest mid-20th Century and makes a strong case for the often overlooked middle America development of these languages. Landscape architect Ron Henderson poetically situates the house within the surrounding natural setting and Hilary Lewis, the Chief Curator and Creative Director at Philip Johnson’s Glass House in New Caanan, Connecticut, reflects on the similarities and differences of the Edith Farnsworth House’s most famous disciple. Subsequent chapters include oral histories by Lord Peter Palumbo and Dirk Lohan, Mies’s nephew and a significant architect who worked under Mies prior to establishing his own firm. Finally, the book includes a portion of Edith Farnsworth’s memoirs that discuss the project’s genesis, construction and lawsuit.

The Edith Farnsworth House at dusk, photographed by George Lambros, 1996. Image courtesy Phaidon / Monacelli.

Additional essays by Sabatino chart the blossoming and disillusion of the Edith-Mies relationship from partners in the development of the image of modern living, to reluctant patron and then adversaries as the project became involved in a prolonged lawsuit. He chronicles the important role of Lord Peter Palumbo in saving the structure from ruin with his purchase in 1968-72. The essay charts Palumbo’s real time education of how to sensitively restore an historic structure following the catastrophic flooding of the Fox River in 1996 and how his evolving commitment to preservation and stewardship was then applied to two other troubled modern masterpieces, the Kentucky Knob residence by Frank Lloyd Wright in the Allegheny Mountains of Pennsylvania and Maisons Jaoul by Le Corbusier Neuilly-sur-Seine outside of Paris. Sabatino also documents how Palumbo, prior to the sale to the National Trust for Historic Preservation, developed the property and slowly opened it to the public with the construction of a Visitors Center and the launch of the Sculpture Walk. Sabatino concludes the history with an account of the frantic scramble to purchase the house at a dramatic auction by a consortium of fundraisers including the Friends of the Farnsworth House, the Landmarks Preservation Council and the National Trust for Historic Preservation after the State of Illinois declined to purchase the property due to financial problems. This monograph is a thorough and engaging overview of the history of one of America’s most breathtaking, inspirational, architectural treasures.

David Sundry is Architecture section editor of Bridge.

Like what you’re reading? Consider donating a few dollars to our writer’s fund and help us keep publishing every Monday.