INTERVIEW: Darya Foroohar: “My Eyes, Your Gaze” Blends the Personal & Political

Darya Foroohar. Image courtesy the artist and Bridge Books.

INTERVIEW: Darya Foroohar: “My Eyes, Your Gaze” Blends the Personal & Political

Foroohar embraces the messiness of living in a gendered body

Darya Foroohar, “My Eyes, Your Gaze”

Bridge Books

Hardcover, $25

By Emma Janssen

My Eyes, Your Gaze, a book by my friend Darya Foroohar, begins with an intense discomfort with the body. “I always feel weird looking in the mirror,” Foroohar writes, the illustrated version of her leaning towards a mirror that glares back, both suspicious of the other. “My body has changed so much that no version of me looks right anymore.”

It’s a sentiment that I think many readers can relate to—I certainly do. The cognitive dissonance of looking at yourself and seeing something foreign, surprising, even existentially terrifying. I’m not sure I can name a single young woman, or any-aged woman for that matter, who hasn’t felt some variation of this discomfort with the body.

Page from “My Eyes, Your Gaze.” Image courtesy the artist and Bridge Books.

It’s exhausting and alienating to move through the world this way. In My Eyes, Foroohar looks to political and feminist theory for solace. The book began as a personal, diaristic project, then morphed into an assignment for a class at UChicago, before taking its final form.

“I was feeling kind of sad, so I was kind of writing-slash-journaling in comic form. And then I was writing about walking and stuff, and I was like ‘Oh, this makes me think of this text I read [...] about how gender and the city interact,” Foroohar told me. That text was the 1985 essay, “The Invisible Flaneuse: Women and the Literature of Modernity,” which features in the first pages of My Eyes. Readers begin exactly where Foroohar’s creative process did, considering the visibility of walking through a city as a woman.

From there, Foroohar’s work expands and deviates, working with texts hundreds of years apart in age, including contemporary punk music and the seminal theory of thinkers like Frantz Fanon. Part of the book’s ranginess comes from the context in which Foroohar created it: as a final assignment for a course on global queer and feminist aesthetics. It was important, too, Foroohar told me, to include non-western and non-white theorists in her work as well. No matter the time period, race, or historical context of the theorist, Foroohar brings their work back to the grounded experience of living in a body coded as female in 2024.

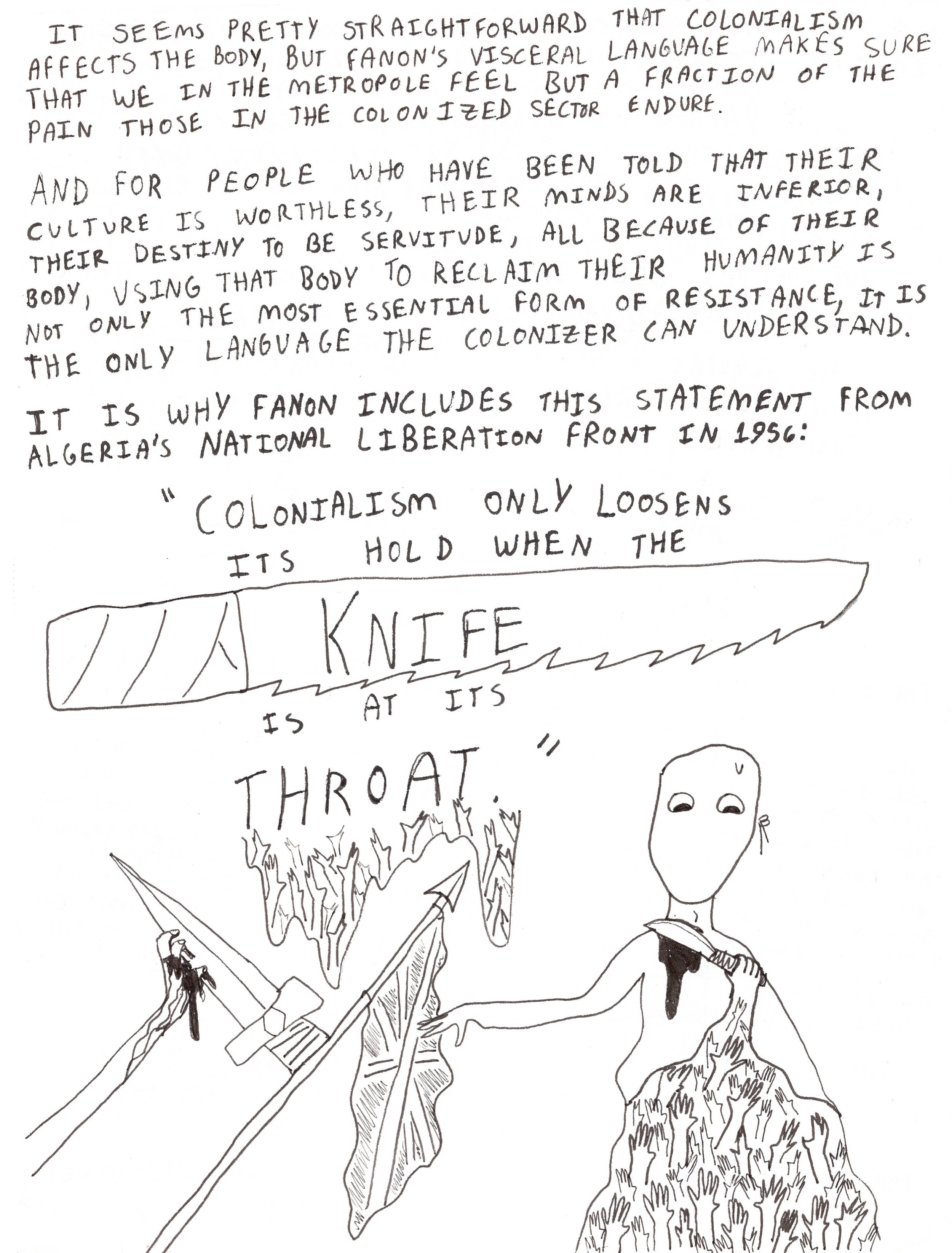

Page from “My Eyes, Your Gaze.” Image courtesy the artist and Bridge Books.

Foroohar renders that experience through her sketchy, black and white style of art while she breaks down the theory through writing. Readers will see her autobiographical sketch (identifiable by its eye bags, short hair, and eyebrows stitched together) surrounded by dozens of eyes, which, representing the male gaze, devour her as she walks down the street, no matter what she wears. Eyes feature constantly throughout the book, watching women and Black people walking across the 2D cities Foroohar draws. When analyzing an essay by Ta-Nehisi Coates, Foroohar depicts the eyes of a Black woman being evicted, which Coates himself described through writing. In her eyes, Coates and Foroohar both show, one can see the inner conflict of a woman reckoning with both the failure of a housing system, the violence of police officers, and her anger at her husband, who cannot express all of the fear and rage she feels due to the danger of appearing as an “angry Black woman.”

From her discussion of American racial politics, white feminism, and the hypervisibility and invisibility of Black women in the U.S., Foroohar moves to a discussion of colonialism in the global context, finding a natural extension of her concerns in the works of Fanon. In his book, The Wretched of the Earth, Foroohar writes, Fanon draws a parallel between the bodies of the colonized and the sectors of the cities into which they are sequestered. It is “a world with no space… a famished sector… a sector that crouches and cowers, a sector on its knees, a sector that is prostrate,” Foroohar quotes. Here, there are no eyes, just scores of disembodied hands reaching over a wall. Later, those same hands come together to form one larger hand, which holds the knife at the throat of colonialism, to use Fanon’s language.

Page from “My Eyes, Your Gaze.” Image courtesy the artist and Bridge Books.

This illustration is one of many in the book that made me stop, breathe, and come back to it. The hands, once separate and forced into the confines of a walled city, came together to form one body, holding the knife of decolonization at the throat of empire. In the hands, one can see the intensity of Foroohar’s illustration; lines where the pen was pushed deep into the page, the dark black splotch of blood she inks.

The art is able to display something within Fanon’s writing that wasn’t explicitly spelled out in words. “Being forced to read so much theory has really helped me,” Foroohar said, describing how works of political and feminist theory have given her an understanding of what’s wrong in the world and how to fix it. “I want to transmit it in a more accessible way.” Drawings that tease out subtext and nuance, depicting them through legible sketches of bodies and cities, are how she makes theory more accessible to her readers.

Foroohar told me that her relationship to her own drawing style has been a complicated one. Her work has a distinct sketchiness to it and is marked by repeated images and words (eyes, hands, and one page that is filled entirely with the word “cunt”). My Eyes is entirely in black pen, while some of her more recent works include color.

Page from “My Eyes, Your Gaze.” Image courtesy the artist and Bridge Books.

“I’ve always been drawing,” she said. “My middle school and high school and college notebooks were covered in doodles.” In high school she wrote a four page comic, but never expanded it. “It would never look as good as it did in my head, and that was really discouraging to me.” Early in college, she took a class where everyone, no matter if they were excellent artists or stick-figure connoisseurs, wrote an eight page comic for the final project. It galvanized her, making her realize that her art style was an asset rather than a weakness.

Writing My Eyes, though, sealed the deal for Foroohar, showing her the value of her work. “This book really changed my relationship to comics in showing me that I can actually do it,” she said. “That my work is good enough for someone else to publish it.” Now, she said, she's “deeper in the comics world” than she’s ever been, bringing her work to festivals, publishing shorter volumes, and experimenting with genre, color, and form.

As the book barrels towards its close, readers meet Pussy Riot and Megan Thee Stallion, both of whose lyrics posit a way of living in a sexualized female body and taking power from it. Through their work, Foroohar invites readers back into the animating discomfort of the body. “Perhaps it is time we returned to our bodies,” she writes. “Sit in them for a while.” In all their messiness and sexiness and genderness.

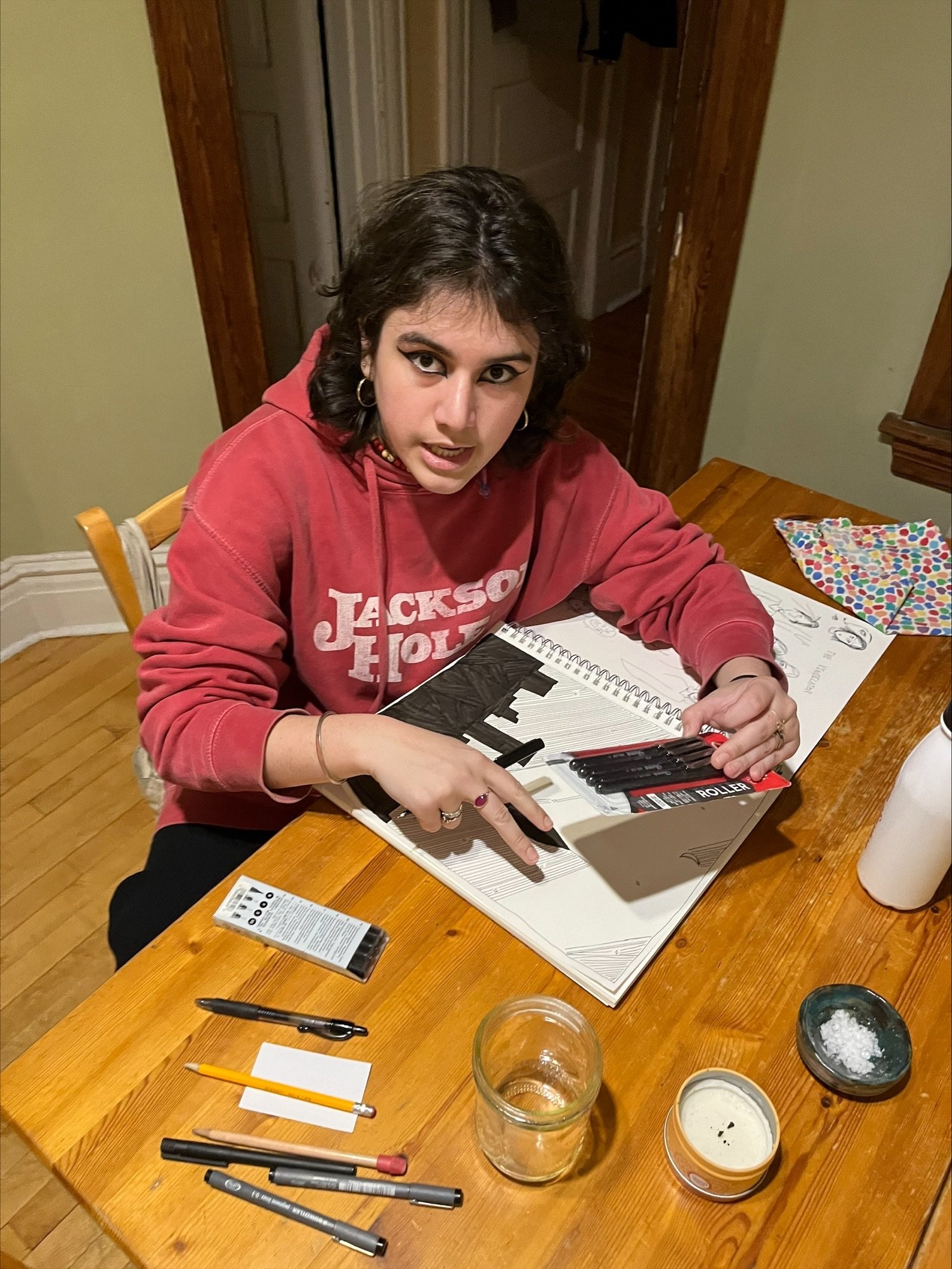

Foroohar working on her notebook. Image courtesy the artist and Bridge Books.

But there’s a comfort to be found in the body, too: “Your hands made this / so did your mind. A product of the person and the body, and the mind, and however you want to relate the three to each other they are all there and they are yours and so is your creation,” Foroohar writes, the shaky figure of a hand drawn next to it.

Art and “creation” more broadly are how we return to our bodies with curiosity and care instead of alienation and anger. Through creation, we remake ourselves. The book ends with a self-portrait of Foroohar waving. She wears a black binder, baggy jeans, and smiles with wide, dark eyes. We, the readers, gaze upon her, but not with the surveillance and sexualization that the beginning of the book discusses. This time, we see her exactly as she wants to be seen.

EMMA JANSSEN, a Chicago-based journalist, is a 2024 Pulitzer Center Fellow who writes about U.S. politics, housing, and abortion rights. In 2024 she graduated from the University of Chicago, where she studied political philosophy and languages, including Dutch, Turkish, and Sorani. She is on a perpetual journey to become a polyglot and can be found reading, chasing after street cats, and swimming in Lake Michigan (weather permitting.)

Like what you’re reading? Consider donating a few dollars to our writer’s fund and help us keep publishing every Monday.