FICTION: “Novel Excerpt,” by Mairead Case

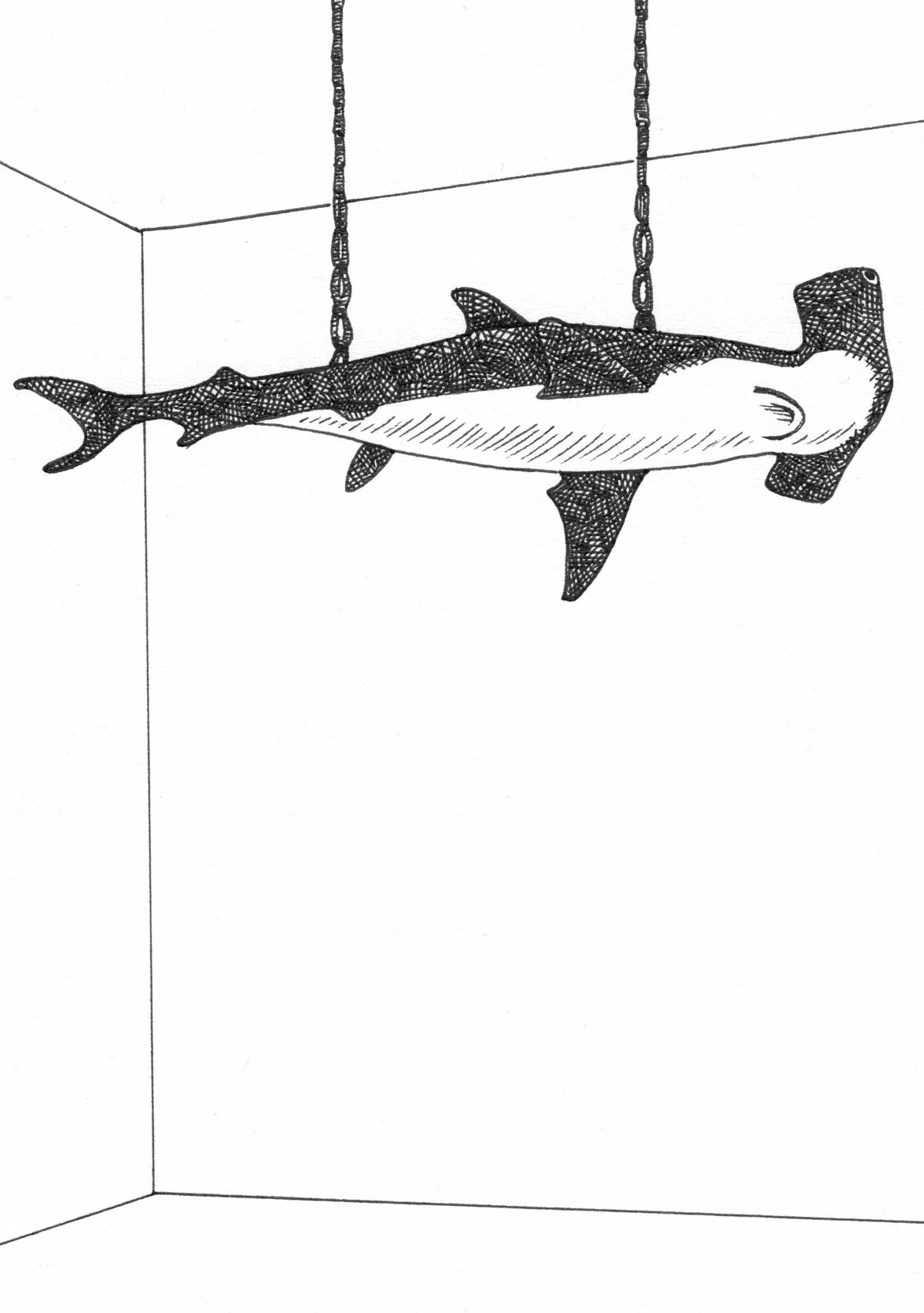

Illustration by Maura Walsh / Black Nail Studio.

FICTION

Novel Excerpt

By Mairead Case

“I am trying so very hard to want the world I have in front of me to want. My heart is beating so fast I swear I could beat the shit out of something quite grand with it.” – Lauren Berlant & Kathleen Stewart

I moved to Chicago because I wanted to make art with my friends. I wanted to find them. My friends. We had always thought the world was ending, and especially then we believed it was ending because of ignorance. A dangerous position, teetering on narcissism, but not an unhealthy one for kids looking for work. I believed art could change worlds—yours, if you were alone, which means if you didn’t belong to the dominant world, and ours. On a fundamental but not always practical level, I considered us as one organism, like how moss softens noise or octopi store ganglia and forty million neurons in each of their arms. I still believe this, that we are one and also not. I believe it for the young and therefore, for all of us.

I started writing this then. I lived in one room, painted chocolate brown, with no closet and someone else’s mattress on the floor. I left a bowl of pickled tomatoes on my desk, which was also a window ledge, and when I came back there was a fly resting on the pulp. I wrote how I felt about the fly, meaning everything, and sent the pages to Chris, because when we left school, we promised each other to be writers. I wanted to prove I never stopped. I never did, but I didn’t need to prove that to anyone but myself. It is important to remember that more than one thing can be true at once. Because of my face, the Polish women would speak Ukrainian to me when I bought my jars and cans and dark bread on the corner. I would smile, put one hand on my heart, and say “neighbor.”

+

Shortly after I moved to Chicago, a friend from school was diagnosed with cancer. I learned about this, also that he had died, when I picked up my phone, which was shaped like a travel-size detangling hairbrush. I saw two other friends had called, one right after the other. It, meaning his death and also our awareness of it, had taken two weeks start to finish. There were lumps in my friend’s armpits and groin. None of us could say more than a few sentences into the electric telephone air, and I realized I needed to sit down. I couldn’t tell you if my body was preparing to fight or if I thought it might be, so I sat down. “Oh my god,” I said, and I was overwhelmed to be alive afterwards. After him.

I was overwhelmed because I felt my friend turning into a symbol, which of course he wasn’t, but I didn’t know how to remember him otherwise. I believed, through a combination of wild good luck, deadass love, and Midwestern Puritanism, that nearly anything—at least, everything I could name—could be fixed through love, patience, and expertise, however because I could not bring my friend back to life, I sat down on the stoop. Some kid had drawn a hopscotch game on the sidewalk. Thirty-seven squares and at the end, a patch of blue sky.

When K. heard I lost a friend, he told me about a friend he’d lost: decades ago, to an overdose. This was a steady pillar of our relationship: something would happen to me, and because we were the same person, it would already have happened to K., and he would help me handle it. Rather, he would tell me how. I had not yet realized that because of who I am and what I do, one major task of my life will be to outlive people, or to remember, to mourn them and then to leave, carefully. Because I did not yet understand this, K.’s friend and mine locked into one. One beautiful, big-living, world-swallowing friend who worked in the dish pit and at Guitar Center, smelled bad, and had swirl-cloud hair. Their faces became one holographic sticker, and our lives, illuminated by its flatness, were poorer now. As our lost men collapsed into each other, I began to collapse my self into K. It was not a conscious choice but the path of least resistance. I believed suffering was noble, love strongest when displaced by a sweetheart’s grief. I believed happiness was, as Willa Cather said, to be dissolved into something true and great.

+

K. had a thing he called Naked Photobooth. It was a special invitation, extended to all kinds of people, though men rarely said yes. It was always the women, always later in the night when everyone had three glasses and hadn’t yet ordered tots. K. arranged his nights, he said, so no one felt tethered to him, though this was a lie because if there were drugs, he kept them. Once I accidentally put his lighter in my pocket and K. screamed at me. He never carried my keys or tickets, because, he said, if we had to run, we might not be able to run together. Every day of the relationship was laced with anxiety, which I thought meant I was important. I thought I was special. The burden of the martyr.

The invitation was to be naked in the photobooth with K. You picked how (shirt up, pants down, a thigh), though he would help you or lick you, if you asked, and you picked who kept the photo strip. K. swore that since it was a vintage photochemical booth, there was no other record. He said being naked was different than being nude and that he only ever got hard for girlfriends, so the invitation wasn’t sexual. K. said consent was powerful, and anyway a dick in a lap is different than a dick in your face. Is it? Can a book transform memory? Can I keep you safe?

Now, I know that we can consent to situations without agency, and that in these instances, children need protection. They need grace. I was a child. K. is more than twenty years older than me. I could have been his child. Sometimes we want things we can’t yet have. I want a world where it is safe for children to desire without being objectified. This world doesn’t fully exist, yet, which means our world is not my own. In large part this is how I know ours isn’t all there is. I never went in the photobooth with K., though I didn’t care if other people did.

+

Sometimes I think about my loneliness like teeth. When I was fifteen, the bones were pushing themselves through my face. It was loud, and it really hurt. Teething is metal, but it is also a process, not an identity. Before the teeth erupt, their edges push along the gums from the inside, like a bassline teasing a room. They push along for weeks, and then they push through. Today, my loneliness sits inside my mouth, and most of the time it helps me. This is not the same as saying I’m grateful for it.

Teeth make notches. They comb and latch and grip. Once I dreamed all of mine fell out, and I thought: well, now you had that dream. People bite into breasts and necks and bread. During the first Selma to Montgomery march, a little girl remembers biting a hand that grabbed her in the crowd. Teeth are also little pieces of sharp, crackable, durable bone. They charm, and they protect. They are small, hard, and true.

+

K. told me to write a book about him. At the time I thought it could be romantic, a way for him to visit from the afterlife. A way to consent to all that. But I have always resisted living to write, the delusional authority of it, the lie of genre, and so I said no. He said I would do it anyway, and now I am. K. also said the odds of me leaving first were far greater. I could get hit by a bus. I could fall into an/other love. I never wanted to go anywhere, though. Not rehab, not the suburbs. Only ever to Chicago. K., who does not have any color photographs from his childhood, smoked two packs of Camel Reds a day and said that whenever he was diagnosed with cancer, he would go to the forest and never come back.

Now, I think my resistance was seeing myself as a victim, which is both a mortifying stance and a boring plot. I do not care about justice for her. I do not think she is more important than you are. I care about story, and I believe in the power of it, of telling yours and having it heard, though I also believe that turning a confession or an admission into a show, meaning that every night you admit it and need to be believed, again, is ultimately an unwell act. Of course, we do things that are unwell all the time. Purity at best is a lie, and at worst it is not something human. What is clear to me: we must not let our stories turn us into monsters to ourselves.

+

You can leave relationships, my therapist tells me. Only our Higher Powers are unconditional.

+

When K. gave me a house key, he also gave me a list of rules, and it was understood, by which I mean I was told, that if I broke those rules, I would lose the key. This was not, he was careful to say, a punishment, but a requirement for anyone with access to his home. He presented as someone who believed in the tension between wild risk and absolute routine as something that could keep him safe, and at the time I found that romantic.

I still do, however now I don’t believe anything that isn’t alive can truly keep you safe. K.’s power was his real safety, which included the number of people he’d seen naked, supplied with pro bono cease-and-desists, and given drugs. There were two locks on the door, and the top one was never used unless someone was having sex, filming sex, or needed you to come back with a warrant. I remember walking through the city and feeling like with that key, I could never be lost.

+

Death is in all of this. “Death makes a new cosmology,” writes Bayo Akomolafe. “Death is not a black hole where things cease to be.” What, he asks, would it be like to treat “grief as power? Even our hopelessness as a form of decomposing and falling away that is sacred.” I think this is different than needing pain to trust, or mistaking pain for intuition. I think, as Saint Chiron wrote, that many people in political power right now are afraid of death, because it will take away their money and influence. This is also why they are afraid of growing old. Ultimately this too is why I have decided never to be afraid of these things. I made a blood pact with myself.

Ultimately writing helps me make sense of everything, and ultimately this is not a purely narcissistic process, because I have the good sense to step aside when equity is at stake. I write for me, I write for you, and together we make a sound with no fixed center. Sometimes we cut out rot and make a new shape. This is a hopeful process.

I think a lot about the poem Elizabeth Bishop wrote for Buster Keaton. In it, she imagines “a paradise, a serious paradise where lovers hold hands / and everything works.”

“I am not sentimental,” the poem ends.

“Yes risk joy,” writes Louise Glück, in a another poem. It starts “I did not expect to survive.”

+

K. loved labyrinths. He loved the expanse and collapse of them, how a container could be immense but also intricate. His apartment was like this, even beyond the shrine. On the top floor, which was where K. spent most of his time, every wall was covered in mirrors or books. The futon in particular faced a full wall of mirror, which meant that if you sat next to each other you saw yourself, the cat, anyone clomping up the stairs. K. watched himself in it constantly, and I watched him too. He said he saw better from the corner. In those days I felt powerful, but also invisible, so I started wearing brighter colors, higher heels, glitter body spray. It was always lizard-hot in K.’s apartment, and specifically stocked: peppermint patties, Folgers coffee, chemically-sweetened cherry cake, and cheese popcorn. Outside of this K. lived on cigarettes, cocaine, and cheeseburgers. Describing him feels violent, like pinning a beetle.

Every surface was occupied or decorated, leaving no perceived emptiness, which meant I often emptied my head to compensate. I liked sitting in the rope chair, where I could gently swing and keep my back to the biggest mirror. I didn’t like the illusion of seeing everything. K. found most of his decoration in the alley, or through people who broke up with him or split town. My favorite painting was a woman with green skin clutching poisonous-looking yellow flowers. Above the futon, chained into the ceiling, hung a preserved hammerhead shark, and to the left of it, facing the mirror wall, was a dense crucifix, rescued from a church under demolition and hung with a Christ-sized pink plaster labia K. bought from a punk house puppet show. Unlike my friends’ rooms, which were hung with equally weird objects and found treasure, every object in K.’s home was symbolic, nostalgic, or imprisoned. I felt safe there because I felt nothing could change me, touch me, or bother me.

The best way to escape a labyrinth—which means to get out, not to heal—is to keep one hand on a wall at all times. If the wall hinges on the side of your hand, turn at the hinge; otherwise, ignore it. If this fails, you will have chalk in your pocket, and you can mark the places where you’ve already turned once. When you come to them again, take the other way. As long as you never choose a path containing two trails, you will eventually leave the maze.

I think a lot about whether entering a maze can be seen as consent. As a kid, I never found them fun, on paper or at the playground. For fun, I practiced balance, speed, swinging high. I have more scars because of this. The core truth is that consent cannot be completely given in a power imbalance, by which I mean childhood, not difference. I could not consent to a relationship with K., yet I continued cleaving to him because once we started, everything else fell away. Isolation reinforces manipulation once you become too exhausted to argue, too lonely to change. I believed I was a special, elegant alien because K. said so. I believed there was no other way for me to be loved.

The labyrinth was built to contain the minotaur, who was not abandoned there per se, because they were also offered children and virgins to eat. I imagine piles of bones, though maybe they ate those too, like vultures. The stomach acid of a bearded vulture is one hundred times more powerful than the stomach acid of a human, so much so that vultures will barf in self-defense. The minotaur, who was created when Pasiphae donned a cow costume made of wood and cow skin and fucked a bull in a field, was imprisoned because no one knew how to handle them. They were the only one of their kind. Eventually the minotaur was murdered inside the maze, but I wonder if they didn’t have peace before that, since they were finally alone. In the end, we are all we have.

Mairead Case is a writer, editor and teacher in Denver (maireadcase.com).

Like what you’re reading? Consider donating a few dollars to our writer’s fund and help us keep publishing every Monday.