REVIEW: “Fanny and Alexander” at the Gene Siskel Film Center

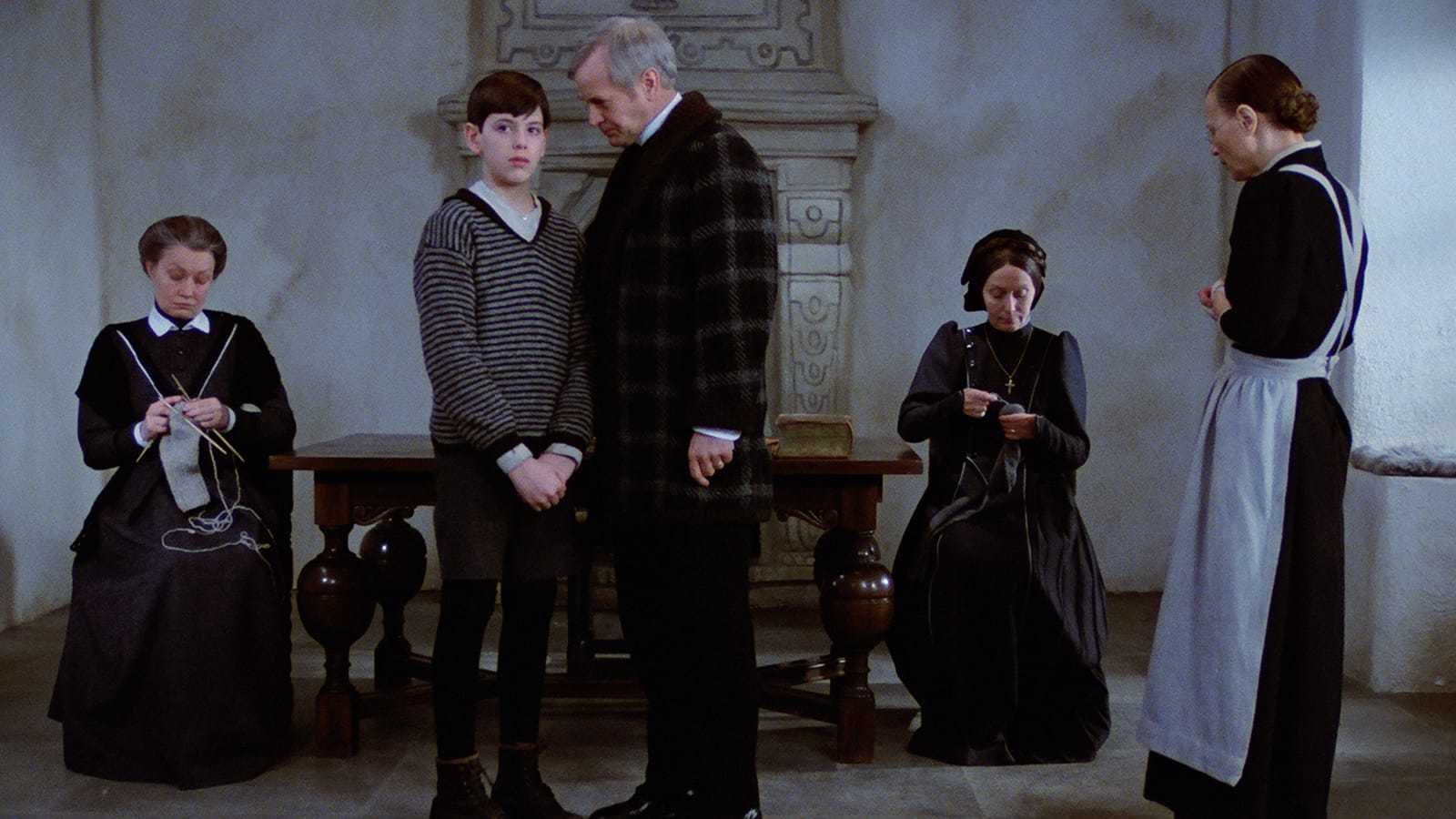

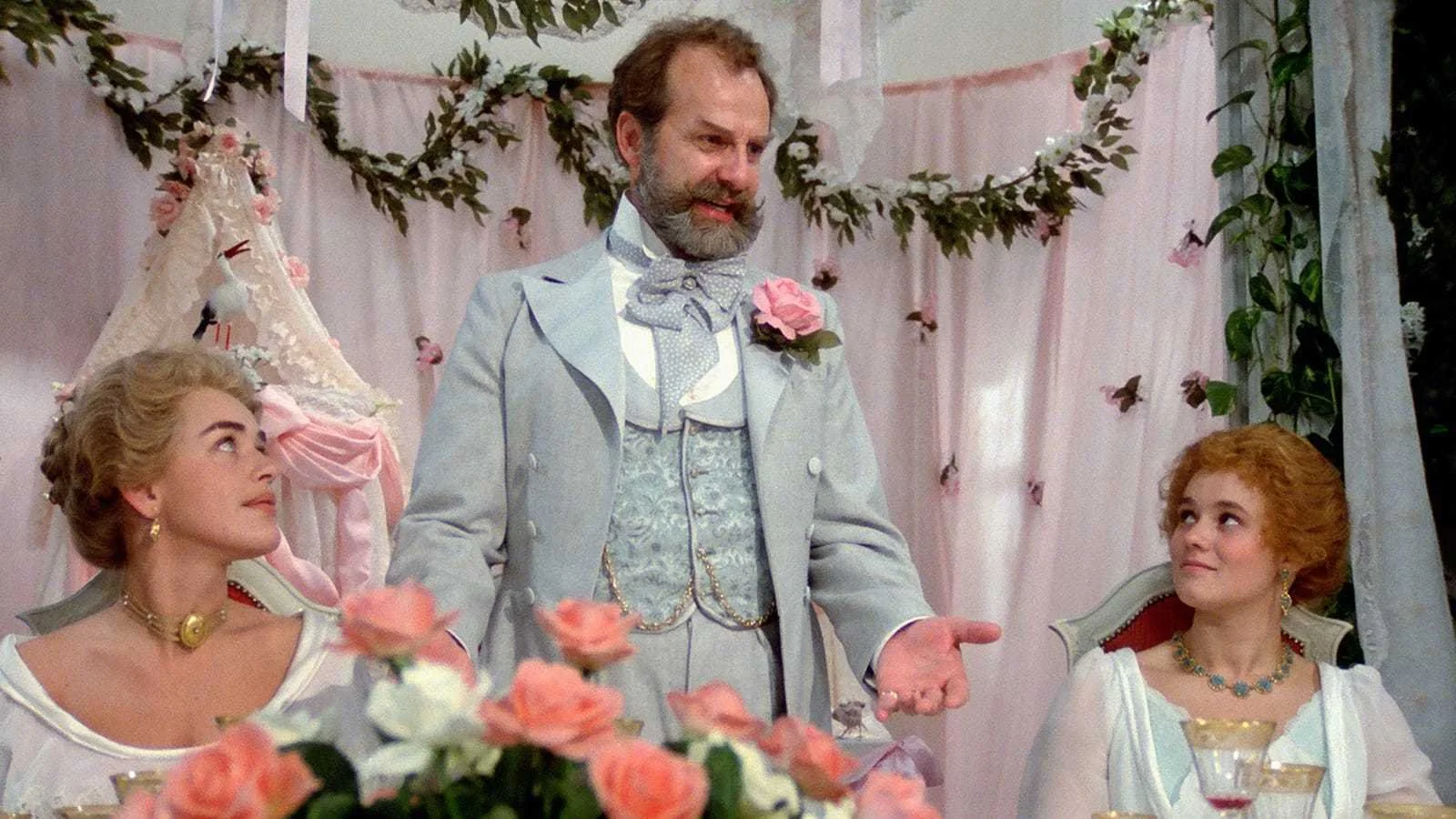

Ingmar Bergman, “Fanny and Alexander,” 1983. Image courtesy of Janus Films.

REVIEW

Fanny and Alexander

Gene Siskel Film Center

164 N State St.

Chicago IL 60601

February 10, 2024

By Ina Megalli

In February, the Gene Siskel Film Center concluded their second annual Settle In series with a screening of Ingmar Bergman’s 1982 epic, Fanny and Alexander. The series, which aired over January and February, put its focus on long films- films that, through their extended runtime, require the viewer to, well, settle in.

‘Long films’ is a far-reaching category- one that can be, more or less, split down the middle. On one end you have cinematic long films, on the other, experimental. Cinematic long films are narrative-driven, and the only thing that separates them from any other movie you’d see in a theater is their length. Fanny and Alexander is one such film, along with most of the other films screened in the series. Experimental long films, on the other hand, are non-narrative, concerned instead with time as a medium within film. Sometimes called ‘slow cinema’, their long, uninterrupted takes and glacial pacing rule the day (1). It’s worth noting that it’s with these experimental films that the average runtime skyrockets (2). The longest film ever made, 2012’s Logistics, boasts a 35-day runtime (3). The Siskel doesn’t distinguish between these two categories, showing both narrative, cinematic long films as well as non-narrative, experimental ones like Ken Jacobs’ Star Spangled to Death (2004), which is composed entirely of found footage.

At five hours long, Fanny and Alexander was by far the shortest film screened this year, paling in comparison to durational giants like Wang Bing’s Dead Souls (2018), which comes in at just over eight hours, and the behemoth of the series, Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s Berlin Alexanderplatz (1980), whose 15-hour runtime was split over two days of screening.

Ingmar Bergman, “Fanny and Alexander,” 1983. Image courtesy of Janus Films.

You got the feeling, in line for the sold-out screening of Fanny and Alexander, that five hours was small potatoes. The couple in front of me had been to every screening this year, and they joked among themselves about what they would do with the rest of their day. I overheard similar conversations throughout the experience- it seems that in its’ second year of life, the Settle In series has attracted a group of dedicated fans. You can definitely see the appeal. Some people jump out of airplanes, go white water rafting, and free climb. This group of cinephiles get their adrenaline fix by turning their phones off and plugging into a workday’s full of subtitles. Either way, the bragging rights are undeniable.

There was a real buzz in the air as we all filed into the theater. It felt a bit like boarding a cross country flight- my fellow moviegoers carried blankets and snacks, and I wondered if I should do some light stretching before getting to my seat. While very plush, the Siskel’s seats are a bit narrow and straight-backed, and much like an airplane, I feared that I would emerge from the experience a bit sore and worse for wear. Unlike an airplane, of course, I could have gotten up and left at any time- crawling over my neighbors and emerging onto State Street to go get a hot dog and see the Bean.

It didn’t feel like much of an option, however. The moment the film began, the Janus Films logo stark against a black background, we were taking off. For better or for worse, this would be where I spent my day.

Now here is something you may not know. Five hours is a long time. The Super Bowl lasts just over three. A flight from Chicago to New York is two with the right headwind. In five hours I could travel from my apartment to Evanston six times. With traffic. Knowing all this, I’ll admit that I was a bit apprehensive that during the movie I would find myself bored. Luckily, I quickly learned one more thing: Fanny and Alexander is not boring.

Ingmar Bergman, “Fanny and Alexander,” 1983. Image courtesy of Janus Films.

Bergman’s semi-autobiographical saga follows the Ekdahl family, a boisterous, dysfunctional bunch of actors, restaurateurs, and alcoholics living in a small city in Sweden at the turn of the 20th century. After the sudden death of eldest brother Oskar, his wife Emilie soon remarries the bishop, to the dismay of her two young children, Fanny and Alexander. The bishop is a stern sociopath whose vicious punishments and militant household quickly prove unbearable for the little family. The Ekdahls must then come together to save Emilie and the children from the clutches of the bishop and his equally austere mother and sister.

The film exists in two versions- the first, the complete edition, originally produced as a television mini-series, the second, a trimmed down (only 3 hours long!) version which was slated for theatrical release. Though longer, the television version includes credits after every act, which allowed us a bit of a reprieve in addition to the twenty-minute intermission at the three-hour mark. People made the most of these credit breaks- the room was quickly filled with chatter and crinkling, some people dashed for the doors in the hope they could run to the restroom in the twenty seconds before the next act began. Despite the runtime, you got the feeling that no one wanted to miss a minute of it. In fact, when the movie was finished, the two people seated directly behind me began a spirited discussion about what could have possibly been cut for the theatrical version.

I couldn’t help but agree with them. Fanny and Alexander seems to me a movie on a tall, thin, tightwire. It walks back and forth- hilarious to terrifying, physical to spiritual, cynical to optimistic. Never spending too much time on either side, Bergman keeps the audience on its toes, demanding a level of engagement that perhaps only the patrons of the Settle In series can offer. I can’t imagine I would have enjoyed the movie nearly as much if I had seen it in my own house- pausing to get a snack or go on a walk or talk to my roommates. It’s a claustrophobic sort of movie- filled with small spaces and crowded apartments, family members talking over each other and jostling for attention. Even the bishop’s house, with its empty walls and echoing hallways, is a small and confined space: bars on the windows, locks on the doors. Viewing it in a packed theater seemed only right.

At the end of the day, I emerged bleary eyed and completely spent. The Settle In series was over, and so was my Saturday. As I boarded the train to go home, I enjoyed my newly earned bragging rights.

While the Gene Siskel has not announced whether the Settle In series will return next winter, they have a great block of upcoming programming, including their ongoing film and lecture series on Climate-Fiction, as well as Technicolor Weekend, in collaboration with the Chicago Film Society. Tickets can be found at siskelfilmcenter.org.

Ina Megalli is a writer and student living in Chicago.

Like what you’re reading? Consider donating a few dollars to our writer’s fund and help us keep publishing every Monday.