REVIEW: The Perspective of Nothingness; Chicago Works: Maryam Taghavi مریم تقوی at the MCA Chicago

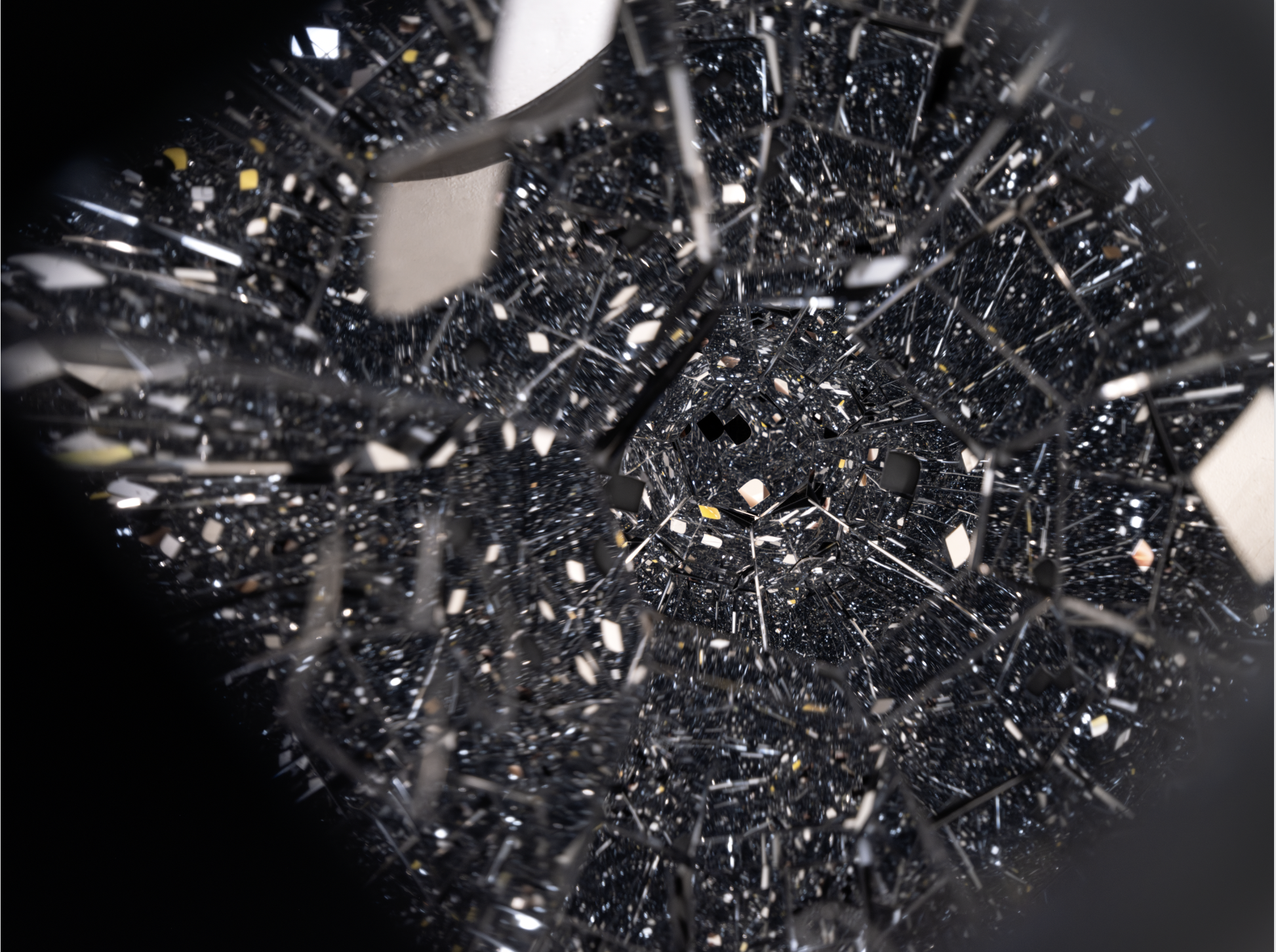

Installation view: Chicago Works: Maryam Taghavi, MCA Chicago. December 16, 2023 – July 14, 2024. Prism view. Photo: Shelby Ragsdale, © MCA Chicago.

REVIEW

Chicago Works: Maryam Taghavi مریم تقوی

MCA Chicago

220 E Chicago Ave

Chicago IL 60611

December 16, 2023 – July 14, 2024

By Xiao deCuhna

All through eternity

Beauty unveils His exquisite form

in the solitude of nothingness

He holds a mirror to His Face

and beholds His own beauty.

— Mawlana Jalal al-Din Muhammad Rumi

A dot in the English language is a conclusion. A period, an ellipse — a dot is where things end. Nothing else shall be said. It is absolute.

A similar absoluteness is present in the Farsi dot, known as the “noghte.” Its quantity and placement define and significantly alter a letterform’s pronunciation and, therefore, its meaning. The noghte gives birth to all meanings in the language, like a seed imprinted with a tree’s DNA in its entirety.

So, what happens if absoluteness becomes abstract, definitions blur into interpretations, and ambiguities replace clarities? What happens when everything is replaced with nothingness and predefined concepts are erased? Is the remainder endless possibilities or unfathomable chaos when all external definitions are removed? Does the perspective of nothingness invite, interrogate, or intimidate?

In Chicago Works: Maryam Taghavi, Taghavi crafted an immersive experience using noghte as the building block in MCA’s angular Turner gallery. Removed from its rigid linguistic context, the noghte is transformed from the absolute definer to abstract indications. The visitors are greeted with a series of cut-outs in the gallery walls in the diamond shape of a calligraphic noghte, as part of a piece called Quadrilateral view (2023). As the viewer peeks into the holes, they fall into an infinite universe of the noghte motif reflected by the prisms behind the walls. Three more prisms can be found throughout the exhibition, with one of them deconstructed onto the gallery’s floor as light reflects off the metal panels onto the wall, and another as a standalone sculpture, gently lighting up its surroundings with warm light seeping through.

Installation view: Chicago Works: Maryam Taghavi, MCA Chicago. December 16, 2023 – July 14, 2024. Photo: Shelby Ragsdale, © MCA Chicago.

Next in the exhibition are the Horizon paintings: large-scale abstract works mimicking the vanishing line where water and land touch the sky. Airbrushed shades of color create delicate gradients that remind viewers of a desert sunset or a misty morning. Atop the colorful background, noghtes form dashes of different lengths, tangling with the viewer’s gaze to form an underlying sense of depth and space. Nothing exists, yet everything is present. In the Horizon paintings, the perspective of nothingness is left for the viewer to determine. Do you see a blurry street and the noghtes bright headlights cutting through an evening fog or the white foam outlining the ocean wave as the water blends into the sky?

Titled Nothing is…, the exhibition reflects Taghavi’s diasporic experience and her inherent investigation of the correlation between position and perception.

The prisms draw references from traditional Islamic geometry, which “is regarded as a manifestation of divine and rational thoughts and the perception of rival’s rational thought and perception of world.” Meanwhile, the Horizon paintings adopt the pictorial treatment of space in Islamic miniature paintings, which has an “absolute dependence on the position of the viewer’s eye” for the pictorial space to reconstruct in a three-dimensional fashion where characters are enclosed and depths resurge. Nonetheless, Islamic geometry is adapted secularly, descending from the sacred space to public interactivity. Instead of signifying a rational, singular truth, Taghavi’s prisms encompass an undefined and uncertain space for the viewer to explore. Similarly, the rigid geometric and mathematical practice used to construct pictoriality in Islamic miniature paintings was replaced by the openness of abstract lines and color shades. Finally, the noghte lost its definitive value and became a pathway and an indicator, utilizing its physical shape and form instead of diacritical value.

Installation view: Chicago Works: Maryam Taghavi, MCA Chicago. December 16, 2023 – July 14, 2024. Horizon. Photo: Shelby Ragsdale, © MCA Chicago.

Where one stands determines what/how one sees. What was considered sacrosanct and rigid gains fluidity under a different light. Taghavi refers to her cultural heritage and comfortably removes it from its original context to assign them refreshed meanings and functionalities. “I do have this thread to this language, to this culture, but it’s really hard to preserve it . . . with the distance that I have from it [and] with the time that we are living in,” Taghavi said in her interview with the MCA. This sentiment is universal in the diasporic community. Living thousands of miles away from our homelands, we constantly redefine, rediscover, and reconstruct our history, heritage, and identity. Regardless of our origin, the diasporas must release what was previously known to intentionally create a perspective of nothingness to make our tradition and heritage relevant to our new homes. The divinity must step off of the altar to allow a new temple to be built.

And off of the altar went Taghavi’s sculpture Heechi. Inspired by Tanavoli’s Heech series, Taghavi’s sculpture shares visual elements similar to Tanavoli’s iconic sculpture series by adapting Persian calligraphy. However, Taghavi added a single letter to the world, transforming the word from a divine nothingness of fulfillment and content (“heech”) seen in Sufi spiritualism to “the nothing as it appears in life’s disappointments or despair” that happens in the mundane. If Tanavoli’s nothingness is an idol to be worshiped, Taghavi’s nothingness is a perspective to be lived with. In this piece, the noghte returns to its intended functionality and is the fundamental transition point from “heech” to “heechi.”

Essentially, Chicago Works: Maryam Taghavi is a journey of transition. Gaze into the liminal space created by the prisms and meditate upon the suspended emptiness of the Horizon paintings. In this exhibition, borders, boundaries, and directions make way for possibilities, connections, and liberty.

Chicago Works: Maryam Taghavi is on view at the Museum of Contemporary Art through July 14, 2024. This exhibition will be the first MCA exhibition to be fully translated into Persian.

Xiao daCunha is a writer and artist living in Chicago and Kansas City, Missouri.

Like what you’re reading? Consider donating a few dollars to our writer’s fund and help us keep publishing every Monday.