Since 1999

Designed by Michael Workman Studio

This program is partially supported by a grant from the Illinois Arts Council Agency. This project is partially funded by the National Endowment for the Arts.

Bridge is a proud member of the following alliances:

Welcome to Bridge. Only the most recent season of magazine articles is available here. Please click here to create an account & access past articles, general archives, the new Bridge Video streaming service, also updated weekly in-season, & more.

Featured from the archives: click the poem to read the second of two poems from Szymborska featured in Bridge V1N3, pages 106-107.

INTERVIEW/REVIEW: Jamillah James, Co-Curator: Yoko Ono, “Music of the Mind” at the MCA Chicago

The first thing I encountered at Music of the Mind wasn’t an artwork, but a pair of visitors standing before one. They cocked their heads, whispered, then finally announced that they “just didn’t get how this could be art.” Their skepticism wasn’t malicious, it was simply confusion, mild irritation even. Yet the scene struck me as a perfect entry point into Yoko Ono’s practice, because this moment of grappling is not a failure of the exhibition but the mechanism through which it succeeds. Music of the Mind is built precisely for viewers like them, people uninitiated into the world of conceptual art, who expect clarity and receive provocation instead, who arrive at a museum wanting to see objects but instead are asked to think, imagine, touch, and complete the works themselves. Ono has always aimed to “bring the inside out,” to make the viewer’s interior reactions part of the artwork, and here, that dynamic unfolds in real time. The exhibition stages a space where unfamiliarity becomes activation and where skepticism is not an endpoint but the beginning of participation.

REVIEW: Scott Burton, “Shape Shift” at Wrightwood 659

Scott Burton the artist has multiple points of entry. One may come to him by way of his work as a performance artist, a conceptual artist, a post-minimalist, a furniture designer, a public sculptor, a curator, or an art critic. And yet to brush up against Burton and reduce him to any one of these identities above is surely to miss the point. Scott Burton is a verse.

REVIEW: Olivia Kan-Sperling, “Little Pink Book: a bad bad novel”

Little Pink Book: a bad bad novel is “wrong,” like how some guilty pleasures are “wrong.” Through her fan fiction and multidisciplinary novel, Kan-Sperling asks, why, in our attempts to discover ourselves, do we as writers and readers want misrepresentation, when it may initially seem impractical or harmful to explore? She takes readers to ugly and confusing situations that are somehow still beautiful, entrancing, and funny, where the violence isn’t glamorized by the overt aesthetics at play. In doing so she makes contemporary literature look like a prude—visually, linguistically, and thematically. I had never seriously considered that the novel could be more than tiny words typed out with black ink on a white page—until my time with the novel’s two main characters: Limei, and language itself.

REVIEW: Everlasting Plastics at SPACES

“How can we live without plastics? But, also how can we live without plastics?” Inverse questions like these continue to reverberate throughout conversations about climate change, including in environmental humanities and Anthropocene centered art exhibitions. In addition to these questions, SPACES’ current exhibition Everlasting Plastics considers the complexities of human relations with plastics and the ways in which these materials both shape and erode contemporary ecologies, economies, and the built environment. Not highlighted in the opening label, but also thematically present in the exhibition are indigenized worldviews of materiality and land and art making practices of salvage.

REVIEW: Moa Romanova, “Buff Soul”

Wearing hot pink sweatpants and an oversized black hoodie, Moa Romanova, the protagonist (and author) of the graphic novel Buff Soul, looks down at a folding table displaying three rifles, a handgun, and a pack of cigarettes. Moments before, she and her two best friends enter a shooting range in Texas where T-shirts with the slogan, “Freedom has a nice ring to it and a bit of a recoil” hang on a wall. On another wall is a decal that reads “We don’t call 911.” On her first try, one of Moa’s best friends, Lina, styled with bright pink hair and curtain bangs, strikes a lethal shot into the paper torso’s kidney. Throughout the novel, symbols of death and waves of grief haunt Moa as she travels from Sweden (her home country) to America. By exploring grief among such pithy humor and subtle political criticism, Buff Soul becomes an existentially jacked yet heartwarming graphic novel, especially for those in their late twenties seeking some food for the soul.

FICTION: “Rattlesnake” by Kevin B

The reservation is a standing one. Seven o’clock every Thursday. He meets Grace and Brian and Lucinda and Terry and Matt and Matt and Michael. They have their usual table. Grace doesn’t eat. They don’t talk about Grace not eating. She misses when they could smoke indoors. Grace has never smoked in a restaurant. It was outlawed before she was old enough to partake. That doesn’t matter. She knows people used to be able to do it, and she misses when that was the case. When it was possible. The reservation is under his name.

Archie Norris.

It’s not his real name.

The other standing reservation begins at one am. It is not sharp. Sometimes it’s at one fifteen. It’s whenever Grant decides to show up.

Grant is not his real name.

REVIEW: Zahra Stardust, “Indie Porn: Revolution, Regulation and Resistance”

Indie Porn by Zahra Stardust delivers a deeply researched and unapologetically diplomatic exploration of independent pornography as both a creative practice and a site of resistance. Drawing from over 2 decades of the movement’s history, scholarly research, and her own experiences as a performer, Dr. Stardust maps the precarious terrain in which indie pornographers operate. Often caught between criminalization, stigma, all types of censorship, algorithmic discrimination, and the digital world’s ever-present threat of content piracy. Rather than portraying these producers as victims or rebels on the margins, Dr. Stardust centers them as artists, activists, and laborers engaged in a broader struggle over sexual representation, technological access, and economic justice. It’s framed beautifully as a branch of performance art, normalizing the discussion in and of itself. In all frankness, it feels like a crazy read amid the political moment we’re in where there’s currently a bill moving in the legislative branch of the United States government considering a full national ban on porn (May 2025). Even so, that is ultimately what the book is about: everything that led us here and even suggests methods for meaningful change.

REVIEW: Sophie Calle, "The Sleepers"

As much as Sophie Calle is known as a photographer, she has also always been known as an artist’s book-maker. Well, not an artist’s book-maker exactly, since artist’s books are often unique art objects themselves, but instead cast in Calle’s conceptions as compendiums of an idea. Often nearly journalistic efforts at explorations of intimacy that guide so much the project of her lifelong artistic curiosities, I recall going through no less than three copies of Exquisite Pain, each volume stolen, absconded with, ripped from my (now somewhat onerously cumbersome) library, with its succulent, near-blood red, gilt-edged pages. I miss every stolen copy, and still can’t help but harbor some pang of resentment for each of the thieves.

Calle’s work merits such ardor, of course, as it is almost designed to elicit it. My first encounter in person with Calle’s work, for example, was as an art critic visiting the 2007 Venice Biennale, where she represented France with "Take Care of Yourself," an installation inspired by a breakup email she received, which concluded with the phrase "take care of yourself."

REVIEW: Fail Back—Fail Better: Hal Foster, “Fail Better: Reckonings with Artists and Critics”

For some years now critique in general, and art criticism in particular, have not only been under attack but, in many circles, outright dismissed. The sources of attack span the full spectrum from bullies and commentators on the right to the inquisitors on the left. And the complaints are numerous: value is often determined by market position and little else and cultural institutions dependent upon corporate and foundation sponsorship, back away from debate. And, ironically, over the past few decades, the post-structural critique of modernism has resulted in a cultural moment where critique is not only rejected but it has been posited that critique is not possible. This movement questions interpretative structures and results in a refusal of authority that undercuts critical evaluation. Judgement is rejected. The moral right of the critic is denied. This unharnessed skepticism is extended to any position or perspective that serves as a basis in which many people in this society are able to speak on another’s behalf. The only surviving position is one of lateral relations, a comparative side-by-side model barely distinguishable from anthropology.

Into this moment, Hal Foster, currently the Professor Art and Archaeology at Princeton, enters the foray once again with a new collection of forty revised essays titled Fail Better: Reckonings with Artists and Critics. The collection is not a history but a gathering together of articles from various publications; journals, reviews and exhibition catalogues that are either hard to find or hidden behind paywalls. The title is a quote from a late Samuel Beckett novella entitled Worstward Ho—“No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.” And it is an apt motto for another attempt to provide a critical account of current cultural practice.

FICTION: “Grandpa Would’ve Wanted It” by Hunter Prichard

Business had slowed since sundown. Thad stood tall and straight-backed at the register. The regulars stopping for sandwiches and beer tried talking with him. It was mostly chatter about the weather or an upcoming hockey game but some of them managed to slip in a comment about Thaddeus Ramz, how good a man he’d been, how sad it was that he wouldn’t ever be seen at the poolroom having a beer or reading newspapers at Dunkin’ Donuts. Thad tried to smile the best he could, thanking them for saying kind things and assuring that his family was alright, that his grandpa would’ve been proud that people missed him.

He leaned against the register staring at nothing when Seth and Ernie came into the store and went to the back cooler. He watched Ernie snap a chocolate bar off the shelf as he raised a hand to Daisy Trotter and asked how she was in his dopey drawl. He laughed at Daisy about being so quiet and the smaller girl tried to smile. But she’d been tense and withdrawn all shift, preparing deli sandwiches for the customers with postured absorption. Thad tried talking with her like things were usual but he left her be when she was looking sorry for him.

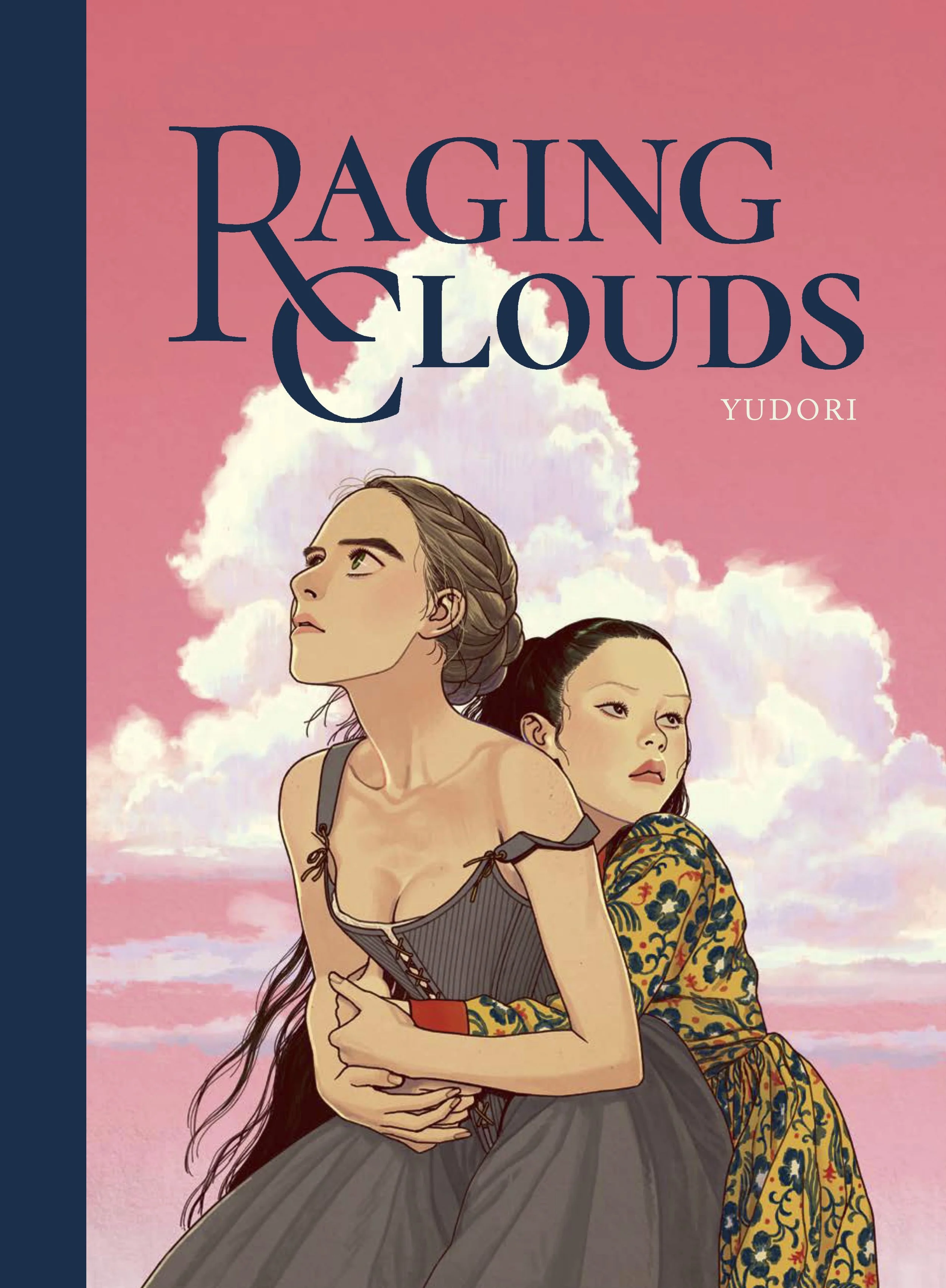

REVIEW: Yudori, “Raging Clouds”

Masterfully challenging Western notions of queer liberation, the debut graphic novel of South Korean comic artist Yudori seems anything but introductory. At the center of the period piece lies a Dutch housewife, Amélie, shackled by a loveless marriage and 16th-century patriarchal norms. Fascinated by physics and the mechanics of flight, she forms an unlikely partnership with her husband’s enslaved mistress, Sahara, as they attempt to design a hot air balloon capable of carrying them both to freedom.

Raging Clouds begins with a classic formula: smart female protagonist in a time when women aren’t supposed to be smart. Yudori delivers the expected amount of feminist one-liners for such a story, satisfying despite the fact that rich white women lamenting married life stopped being revolutionary about ten years ago. “You leave me alone with my own vice, as I leave you to do whatever you like with your slave,” Amélie responds to her husband’s upteenth attempt to quell her scientific experimentation (or as he calls it, sorcery). “See you in hell, my husband.” Equally expected yet satisfying is the result of his later appropriation of her and Sahara’s balloon.

REVIEW: Pixy Liao, "Relationship Material," at the Art Institute of Chicago

Experimental Relationship (2007- Now) is the photography series that experimental photographer Pixy Liao (廖逸君) began quickly after meeting Takahiro Morooka (諸岡高裕), nicknamed Moro, her muse and boyfriend five years her junior. “Relationship Material,” a multimedia exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago, is a continuation of the project, specifically examining their relationship as an artistic material in itself. By re-conceptualizating the idea of a relationship as a physical material, rather than an abstract idea or a goal with pre-determined touchstones, Pixy presents relationships as bodily, temporal, various, contingent, and having creative inclinations. In doing so, Pixy reclaims her relationship with Moro from the presumptuous heteronormative ideologies that plagued her upbringing in Shanghai, China and turns it into art.

FICTION: “Milardo” by Joseph M. Faria

Walking towards the tavern at dawn, an old man named Milardo carried his bag. As he approached the squat white building with its bright red shutters burning in the morning sun, he turned his face away. He looked over the wooden fence at the cows grazing. He wondered what it would be like to be a cow, lazing all day in the wide, open green pastures—not a care in the world. But then the bag, as if sensing his reverie, seemed to weigh heavier on his shoulders. It began pulling him towards the bar. He walked into the place. A square patch of sunlight showed through a small window and fell over the counter. The old man dropped the bag at his feet and nudged it into the shade where the sun could not get at it. He ordered a cup of coffee just as one of the patrons clapped him on the shoulder.

REVIEW: Little Beasts: “Art, Wonder, and the Natural World” at the National Gallery of Art

REVIEW: A Siren’s Invitation: Fabiola Jean-Louis, “Waters of the Abyss” at the Chicago Cultural Center

Imagine an aquatic realm deep in the oceans, where light trickles away into silence and somberness. It’s likely not pure darkness, as land dwindlers such as ourselves might speculate. Instead, colorful hues gleam off corals, shells, and pearls, caressing castles, caves, trenches, and temples undiscovered by human eyes.

Above the ocean, fishboats pass with the blessings of Agwé, the water deity. Under the waters, lost spirits found their eternal home following the mermaid’s guiding melody.

That is the spiritual nation described in Haitian Vodou beliefs.

That is the world presented in Waters of the Abyss: An Intersection of Spirit and Freedom at the Chicago Cultural Center.

In this exhibition, Haitian-born, New York-based conceptual artist Fabiola Jean-Louis created a series of papier-mâché sculptures and paper-based textiles to materialize erased Afro-Haitian identity and history using Vodou mythologies as the vessel.

REVIEW: Alex Katz, "White Lotus," at GRAY Chicago

Upon entering Gray Gallery to view Alex Katz’s exhibit, White Lotus, my gaze is parted by a blue sea of large horizontal paintings and two sections of folding chairs, set up church-like, that merge into a small distant painting hung in an alcove due north of the entrance. This double framed painting, Study for White Lotus, provides a snapshot to a doubling of two subjects—a couple rendered twice—a white skinned, brown-haired man and woman. He is bearded and balding in a white t-shirt. She is neatly coiffed in a cropped bob wearing an aqua blue sleeveless top that matches the landscape. In this seaside social scene, a moment is doubled against a single horizon line which vanishes in the extended sequence of enlarged paintings that bracket it.

REVIEW: Christina Kimeze, “Long Loops,” at Hauser & Wirth

REVIEW: A Rare Glimpse of That Single Fleeting Moment, “Blondell Cummings: Dance as Moving Pictures” at the Chicago Cultural Center

Merce Cunningham famously said, “You have to love dancing to stick to it. It gives you nothing back, no manuscripts to store away, no paintings to show on walls and maybe hang in museums, no poems to be printed and sold, nothing but that single fleeting moment when you feel alive.” This ephemerality also means that tracking dance’s history, especially before the advent of the iPhone, can be a Herculean task. For the average choreographer and performer with no access to academic resources, just trying to educate oneself about the art form’s history and some of its historical figures that are not easily accessed or even represented on the internet, is daunting. That is why the recent exhibition at the Cultural Center: Blondell Cummings: Dance as Moving Pictures (originally co-organized by Art + Practice and the Getty Research Institute) and organized here in Chicago by Elise Butterfield, Curator of Exhibitions at DCASE, was such a gift. The event showcased Blondell Cummings’ independent work in movement and video. Cummings, a student of dance, photography and film grappled with ideas of how movement, a 3-dimensional live art form could also be as powerful in a 2-dimensional medium. Her early studies searched for that place of compromise wherein the best of both methods were able to surface and the energy of the body and the details of the dancing would leap off the screen.

INTERVIEW: Pattern Recognition: Bob Faust on “Wallwork (iam an Artist)” at the Intuit Museum of Art & “Wayfindings” at the Joint Public Safety Training Campus and Boys & Girls Club, Chicago

As part of Intuit Art Museum’s recent reopening, Chicago-based artist and designer Bob Faust unveiled a striking new architectural intervention that reimagines the museum’s façade as both signal and symbol. Wrapping the building in bold, layered imagery drawn from works in Intuit’s permanent collection—including pieces by Henry Darger, Mr. Imagination, and Pauline Simon—the project draws passersby into playful yet reflective encounters. From afar, the vinyl wrap suggests modernist patterning, but closer inspection reveals figurative fragments and gestures that hint at the stories inside.

While different in scope from his recent Wayfindings public sculpture on the West Side, both projects reflect Faust’s commitment to building visual infrastructures of participation, layered with memory, identity, and place. The Intuit project stands as a quietly radical gesture—an outward-facing museum façade that listens back. Bridge Couture Editor Kristin Mariani sat down with Faust to discuss these projects and more in the interview below.

Kristin Mariani: I am so excited to talk about Wayfindings and your façade intervention at the Intuit Art Museum.

Bob Faust: Thank you, thank you.

Yes, yes. Would you like to start with the more recent Intuit Art Museum project, or Wayfindings? Do you have a preference?

Let's go to Wayfindings first, I think. It has a lot in it.

Great, It's such a beautiful project. Let's begin with community engagement. Wayfindings is a major public art initiative that deeply involves community interaction, located on the city’s new Joint Public Safety Training Campus and newest Boys & Girls Club at 4433 W. Chicago Avenue in the Austin neighborhood. Can you talk about how this participatory process influenced the design that you created?

Absolutely. It was a big project that took place kind of fast for something as large as it is. It included stakeholders even before anything was done—just the RFP process involved working with the stakeholders. It included: the police department, the fire department, the Boys and Girls Club, Alderman Mitts’ office, and a lot of neighborhood leaders including a few pastors, business leaders, block club leaders, art leaders, and DCASE of course. And then the kicker to it was that there were three architecture firms involved, as well as a landscape architect. So it was a lot of folks that had vested interest and wanted to know that all of their concerns, excitement, and opportunities were going to be acknowledged and worked into the final product.

REVIEW: Modern Myths: “Wafaa Bilal: Indulge Me” at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago

When the MCA postponed the career-spanning show Indulge Me by Iraqi artist Wafaa Bilal for a whole year, some hearsay from my gossip network suggested that it was due to the postponement of a rocket launch. The work in question is Canto III (2015), a response the artist made to a rumorhe heard: Saddam Hussein's political party, the Ba'athists, wanted to launch gold busts of the leader to outer space and directly above Baghdad, so the busts, like a satellite, would forever orbit around Earth and be “watching” Iraq. The installation of Canto III further conceptualizes the materialization of this “crazy” space Saddam project, but with a satirical twist. It imagines sending a miniature bust, equipped with a selfie cam, to just below the orbit: close enough that it would send live feed for a year or so before burning into dust by gravity, but not enough to be granted eternity in space (albeit comically as a piece of space junk).

The Ba’athists’ project was never realized, nor did Bilal’s miniature make it to space. But I wasn’t surprised when unverified intel pointed to that the daredevil artist did seek options to tag the sculpture to some commercial rocket launch. After all, it’s not like artists haven’t done it before. Trevor Paglen did it; recently Eduardo Kac did it too. But there’s something strangely poetic about an imaginary project that stems from a rumor and becomes the subject of gossip for a show. It shrouds itself with irresistible myths that point to alternative realities, where what could have happened becomes the focus of interest.